By: Zachary J. Foster

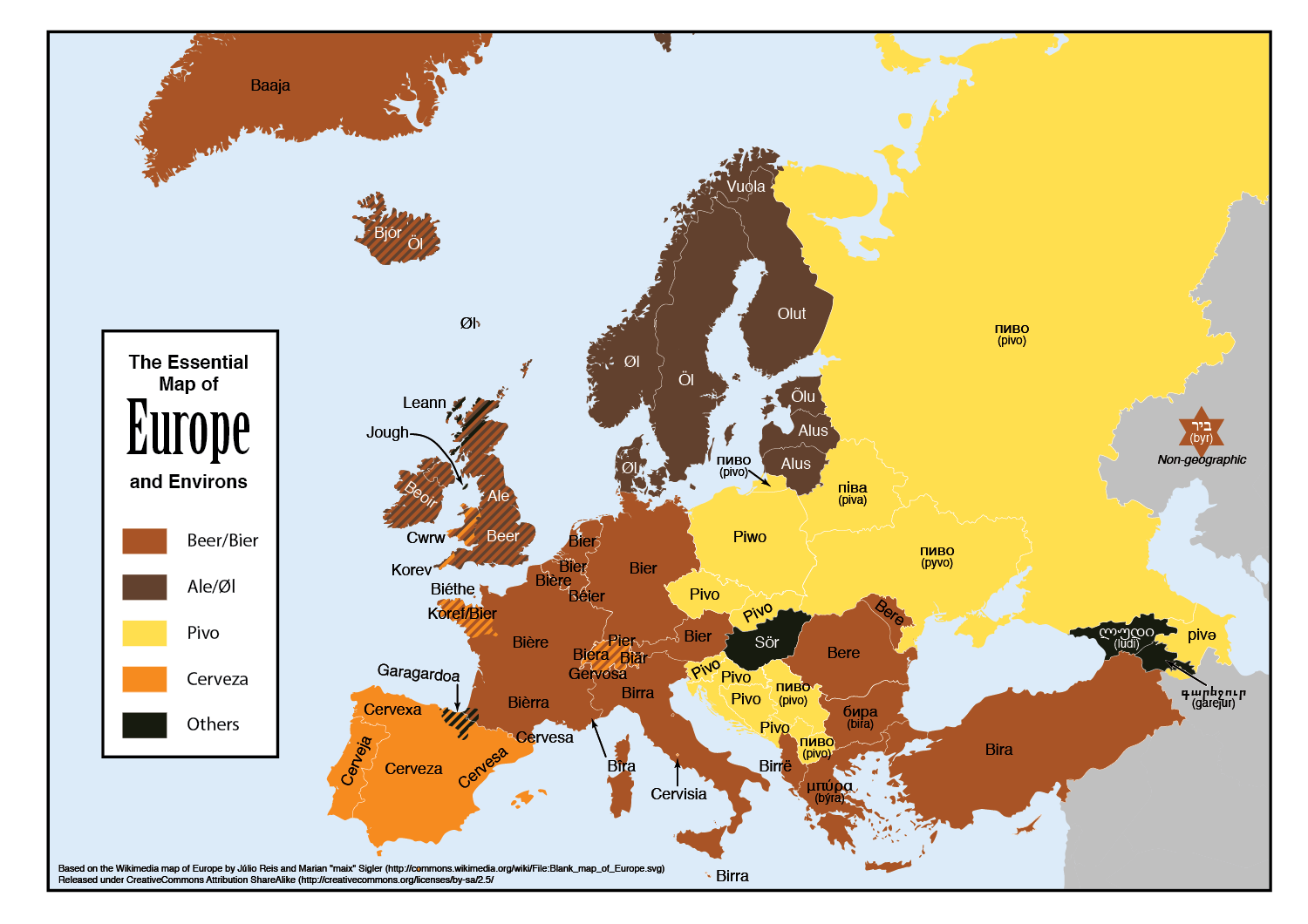

Academics have long concerned themselves with maps of

Palestine. But almost all of the

published literature on Palestine maps–

including the publication of the maps themselves – has dealt with those

maps published in Europe by Europeans.

But what about the Ottoman administrators who ruled over Palestine, and

those (primarily Arabic speakers) that lived in Palestine? How did they imagine Palestine in the

late nineteenth and early twentieth century? The largest collection of ‘Palestine’ maps available on the

web from the Ottoman period, for instance, some 166 maps – contains a whopping

total of ZERO maps produced in the

Ottoman Empire.[1] Below, I would like to offer a few very

preliminary comments on how the Arabs and Ottomans cartographized Palestine in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

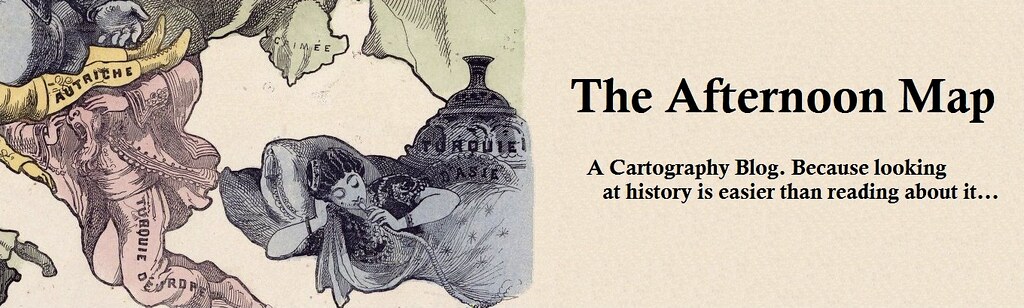

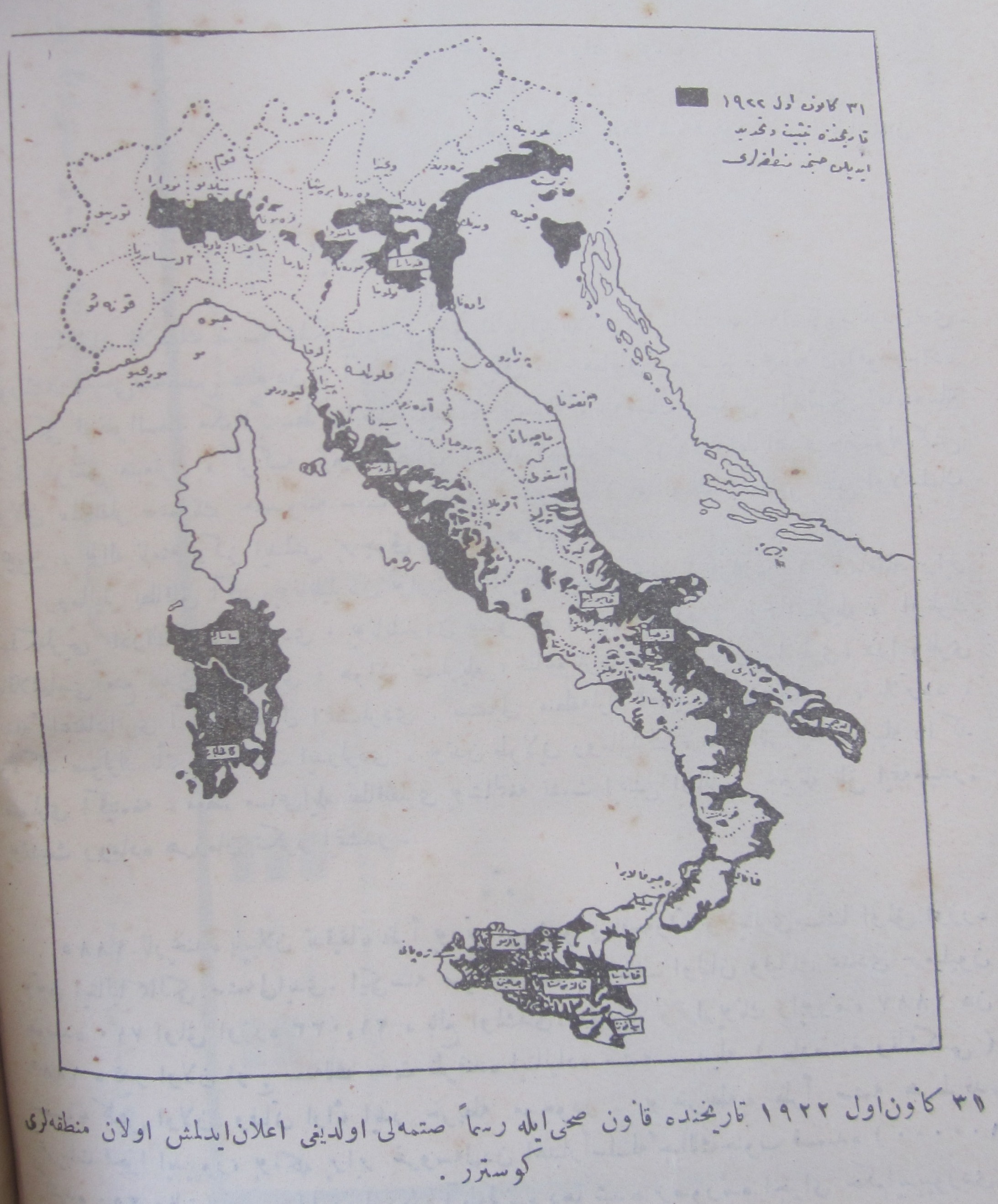

The first map in this collection was published in Filastin Risalesi, an official

publication of the Ottoman army intended to be used as an officer’s manual for

the Palestine region. The

manual itself is a social, topographical, demographic and economic survey of

Palestine circa its time of publication, 1331 (Rumi).[2] It is actually a quite unremarkable

work, and resembles much of the ‘geographical’ literature published in both

Ottoman and Arabic in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The map itself, just as the rest of the

book, is published in Ottoman Turkish, and includes both topographical

features, such as rivers and mountains (the darker the color, the higher the

altitude), as well as all of the major towns and cities.

It is worth noting as well that the version of Palestine

represented in this map bears heavy European influences. In much of the European geographical

literature of the 19th century, as Gideon Biger tells us, Palestine

extended from Rafah (south-east of Gaza) to the Litani River (now in Lebanon),

from the sea in the west, to either the Jordan River or slightly east of Amman

in the East.[3] This is more or less the Palestine that

we see on the map. Notice, as

well, that that there are no lined-borders, only a very general sense of

Palestine as a region. This was

common for the period as well.

Finally, the southern desert, or

Naqb (Negev in Hebrew), is not included in the map, a common feature of

European, Ottoman and Arab maps of the region in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries. South of

Beersheba was wilderness, both beyond the purview of Ottoman imperial

authority, and therefore also beyond the purview of Palestine.

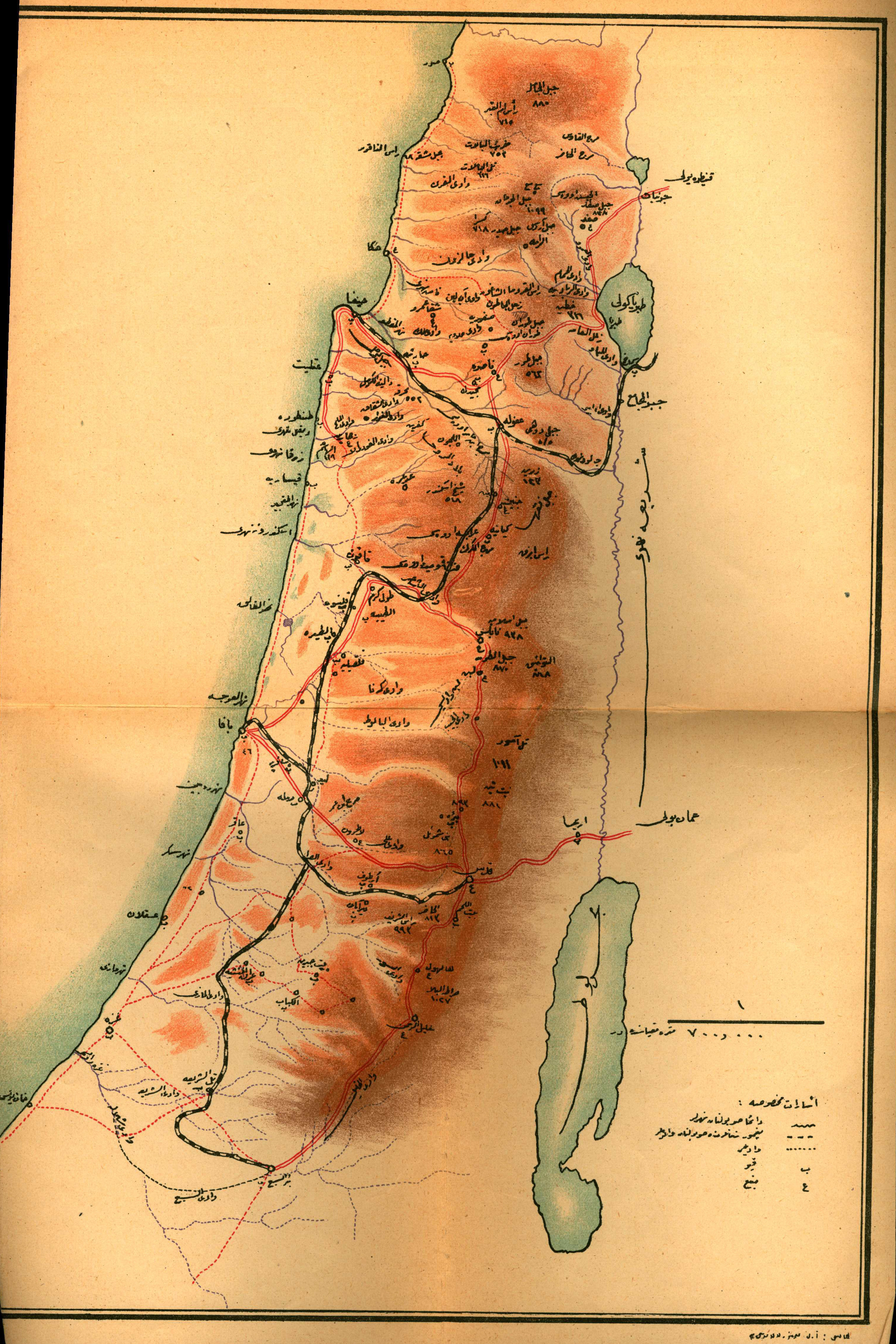

Now we shall turn to another series of maps published in book titled Jughrafiya-i Osmani (1332). The first map of Palestine in the book

is actually not a map of Palestine per se, but a map of Asya as-Sughra (Asia Minor) qabla

al-Milad (before the birth of Christ). This is quite an interesting map insofar as it attempts to

portray the political geography of the region as it looked liked in the

pre-Christ period. Anyone with

even a passing knowledge of European intellectual history of nineteenth century

knows that what was interesting to write about, what was worth knowing,

studying and digging up, was ancient, biblical history. Thus the European growth of ‘bible

studies’ had a profound impact on Ottoman thinking, something that surfaces in

this map here. Hence, the word

‘Palestin’ is written with the letter ‘pe’ in Ottoman Turkish – something I

have only found on this map. It is

also worth noting that the word ‘Palestin’ is written over only the very

southern most area the settled part of the Levant (inside, even the city of

Ahira (Jericho) is north of the ‘Palestin.’ This, again, reflects a classical geographical understanding

of Palestine – which included the southern coastal strip from Gaza to Jaffa, or

the territory inhabited by the Philistines, or ‘Plishtim,’ in Hebrew. Other noteworthy markers on the

map in include ‘Samarya,’ (Samaria), Damasus (Damascus), Palmayra, Tayr and

Yupa (?).

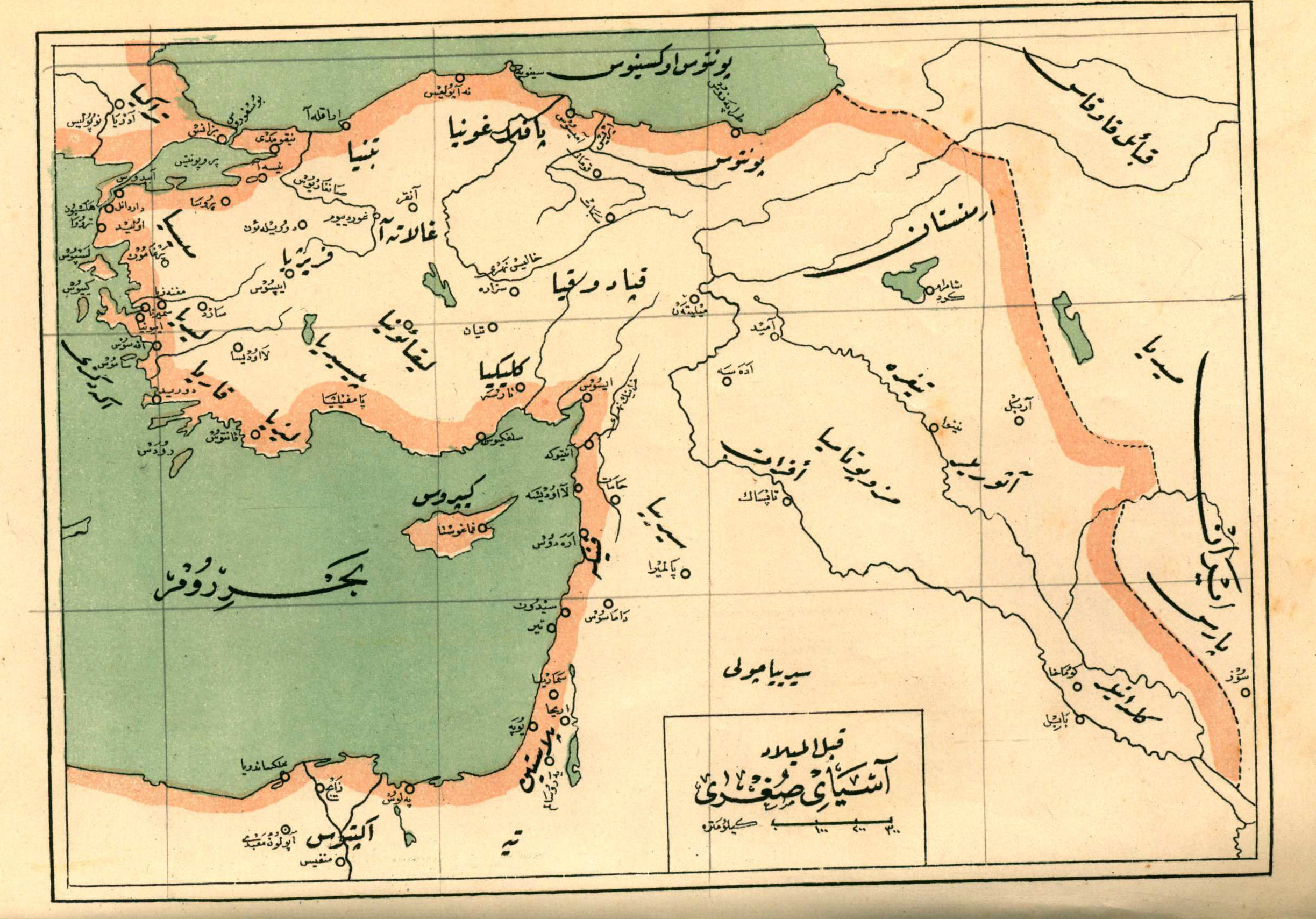

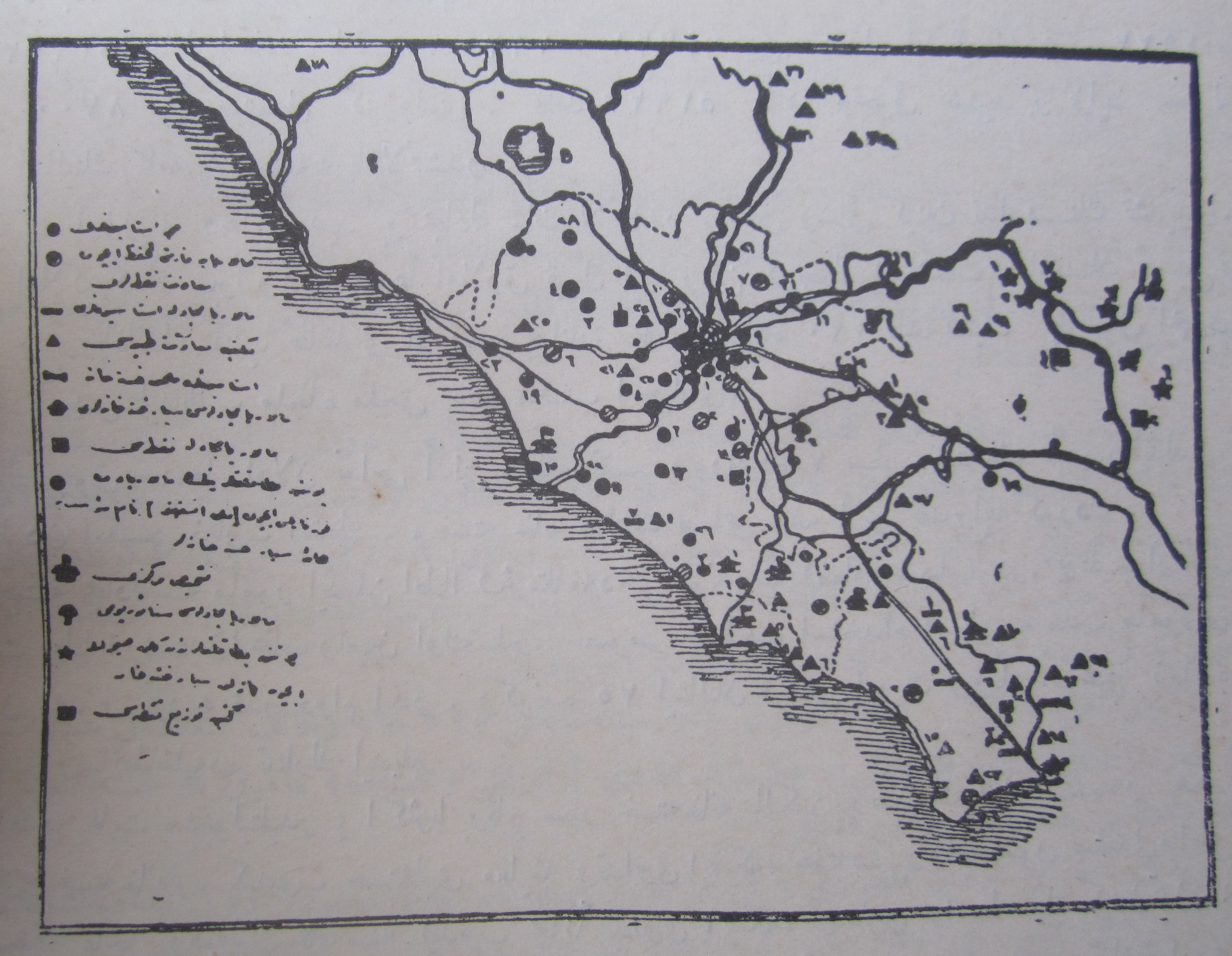

Our next map, like the rest in Jughrafiya-i Osmani (see 90, 101, 104, and 116),

make no mention of Palestine anywhere.

This was not uncommon for the period, as Palestine did not constitute an

administrative district in the Ottoman Empire. Instead, the entire region is labeled ‘Suriye’ in all of

these maps.

Now we turn to another map in Jughrafiya-i Osmani (after p. 98) which does in fact mention Palestine,

now spelled in standard Ottoman (as well as Arabic) way rather than spelled as

a transliteration of the Latin word Palestina. This map claims to be a map of the Ottoman administrative

geography (taksimat-i idariya), which is interesting because, as we just stated above, Filistin was NOT an administrative unit in the Ottoman Empire. The region in which Filistin appears in this map (in between

the two horizontal lines) was in fact the Mutasarıflık

(Mutasarifiyya, in Arabic) of

Jerusalem, of Kudüs-i Şerif. Indeed, it was not uncommon in both

Ottoman and Arabic geographical thinking to regarding ‘Palestine’ as synonymous

with this administrative district.[4] This was a curious blend of the way the

Ottoman administered the region – and the way the Europeans labeled them.

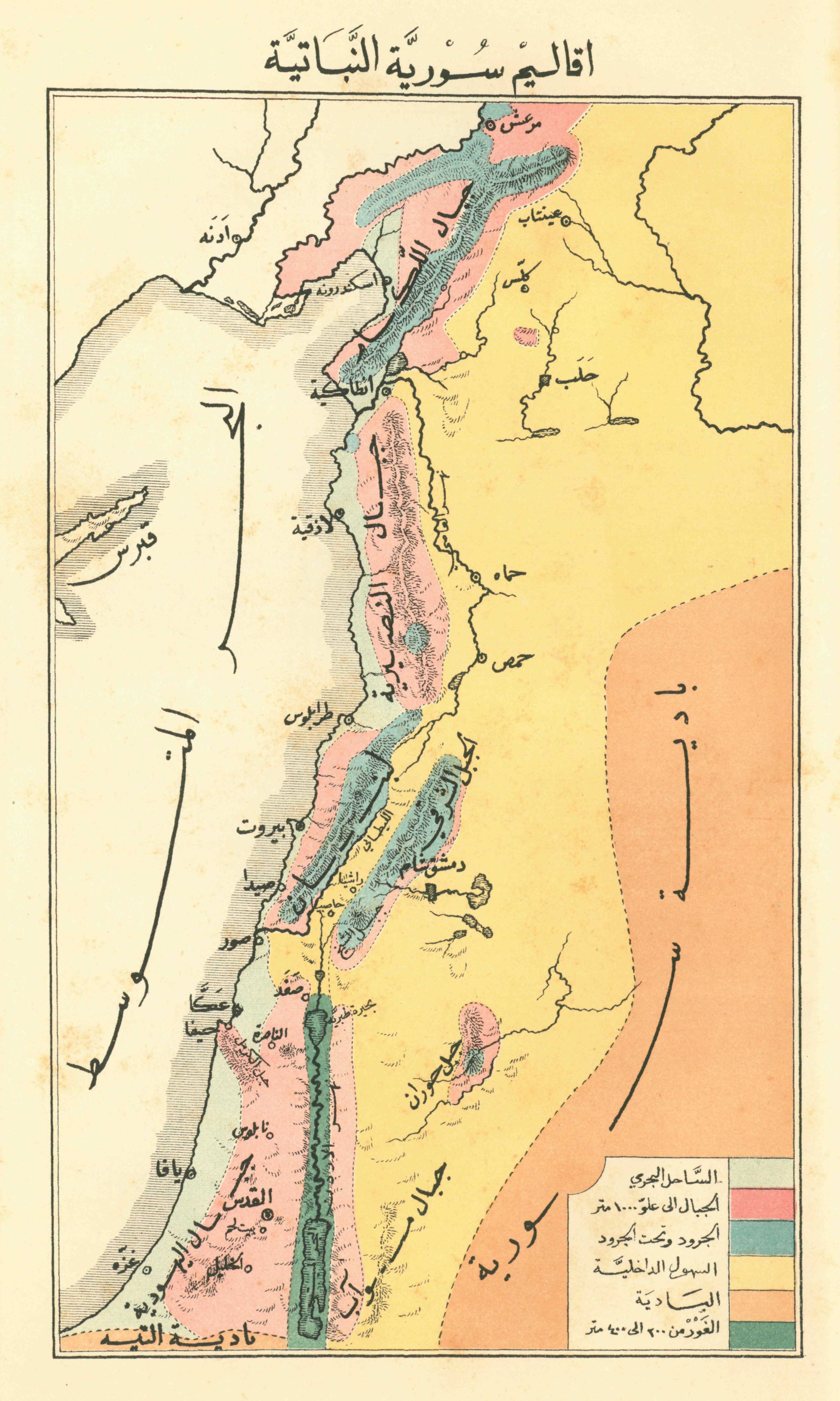

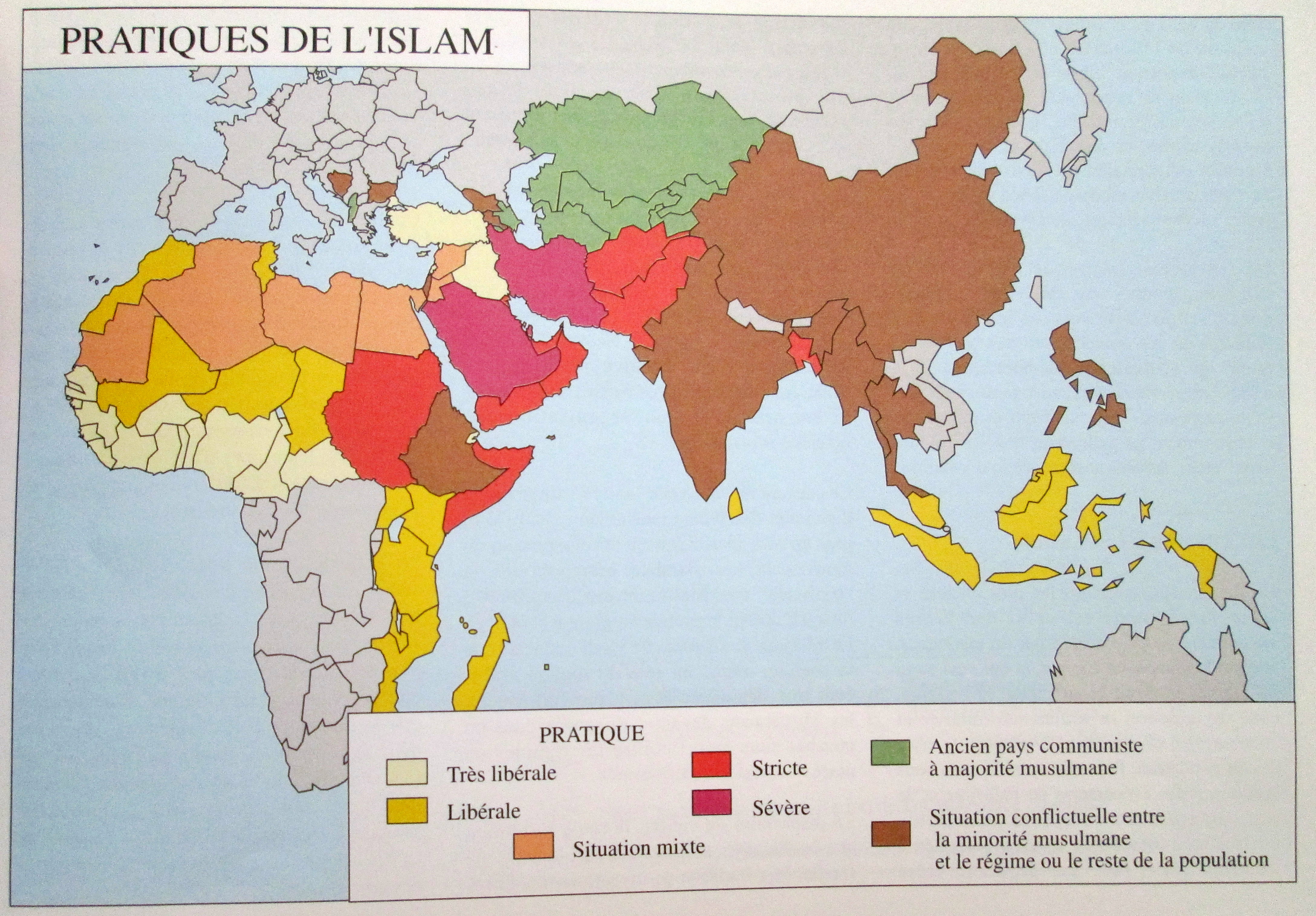

The final map in our collection comes from

George Post’s Nabat Suriya wa-Filastin

wa-al-Qatr al-Misri wa-Bawadiha (Beirut, n.p., 1884), 411 (The Flora of

Syria, Palestine, and the Egyptian Country and its Desert). The title of the map itself is: The Botanical Climate of Syria (Aqalim

Suriyya al-Nabatiyya). Note that Filastin

does not appear anywhere on the map.

Again, insofar as this is a translation of a book by one of most

well-regarded botanists and geographers of Palestine in the nineteenth century,

we once again see just how much the Arabs, in this case, came under the

influence of their European counterparts.

Indeed, this is one of the first books ever published in the Arab

language which included the word ‘Filastin’ in the title of the work, and, low

and behold, it is a translation from the English!

The editors of the OHP have urged me to include a cautionary note to nationalist ideologues on all sides of the spectrum: the 'idea' of palestine in Arab and Ottoman thinking indeed bears heavy European influences, but this a point of scholarly interest, and has no political implications of any kind. Nationalists love to point to the 'indigenousness' of their own nations and national territories -- their originality, their time-immemorialness. But this 'urge' to 'defend' the 'taintlessness' (as if being influenced by Europeans is somehow 'tainted') of their own national spaces, to claim they were not 'mere' 'knee-jerk' 'reactions' to European ideas is itself profoundly reactionary, and embraces everything wrong with nationalism: its claims to ethnic or ideational purity; its ideas of exclusivity, gloriousness and ever-lasting-ness: these are dangerous ideas and have been at the origins of some of the most deadly and dangerous plots in all of human history. Yes, Europe came to dominate the globe in the nineteenth century, with their bibles, guns and MAPS.

[1] This would be The David Rumsey Collection.

[2] For a more

detailed discussion of the pamphlet, See Salim Tamari’s, “Shifting Ottoman

Conceptions of Palestine: Part 1: Filistin Risalesi and the two Jamals,” Jerusalem Quarterly 2011(47)

[3] Gideon

Biger, “Where was Palestine? Pre-World War I perception, AREA” Journal of the Institute of British

Geographers 13(2)(1981): 153–160.

[4] See, for

instance, Sabri Sharif Abd al-Hadi Jughrafiyat Suriyya wa Filastin

al-Tabi‘iyya (Cairo: al-Maktaba al-Ahliyya, 1923), 32; Butrus al-Bustani, Da’irat al-Mar‘arif 10 (1898), 196; Yehoshua

Porath, “The Political Awakening of the Palestinian Arabs and their Leadership

Towards the End of the Ottoman Period,” in Studies

on Palestine During the Ottoman Period, Moshe Ma‘oz (ed.) (Jerusalem: The

Magness, Press, 1986), 351-381; Johann Büsso, Hamidian Palestine: Politics and Society in the District of Jerusalem

1872-1908 (Leiden; Boston : Brill, 2011), 479.