Chris Gratien, Georgetown University

|

| click here for full-sized image |

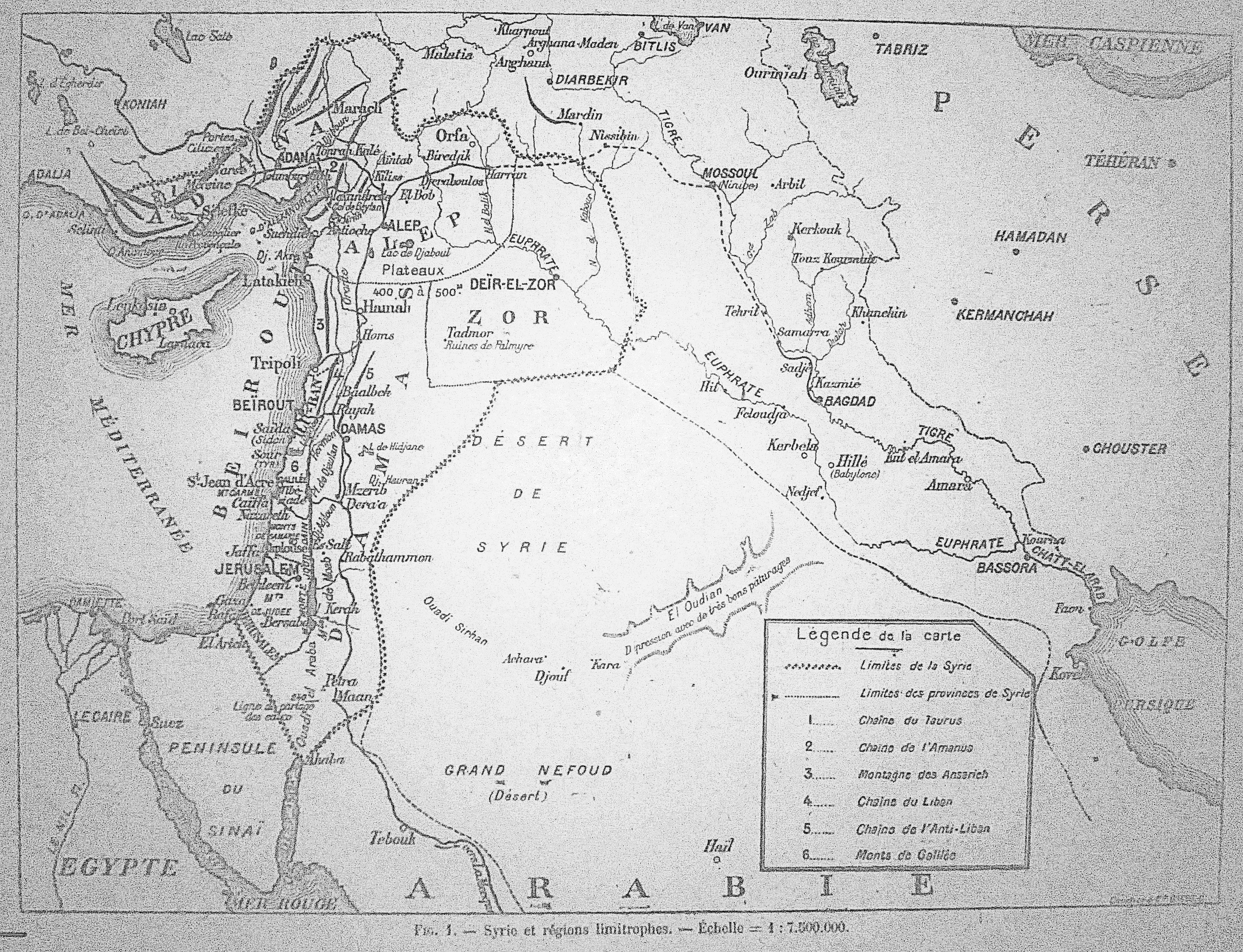

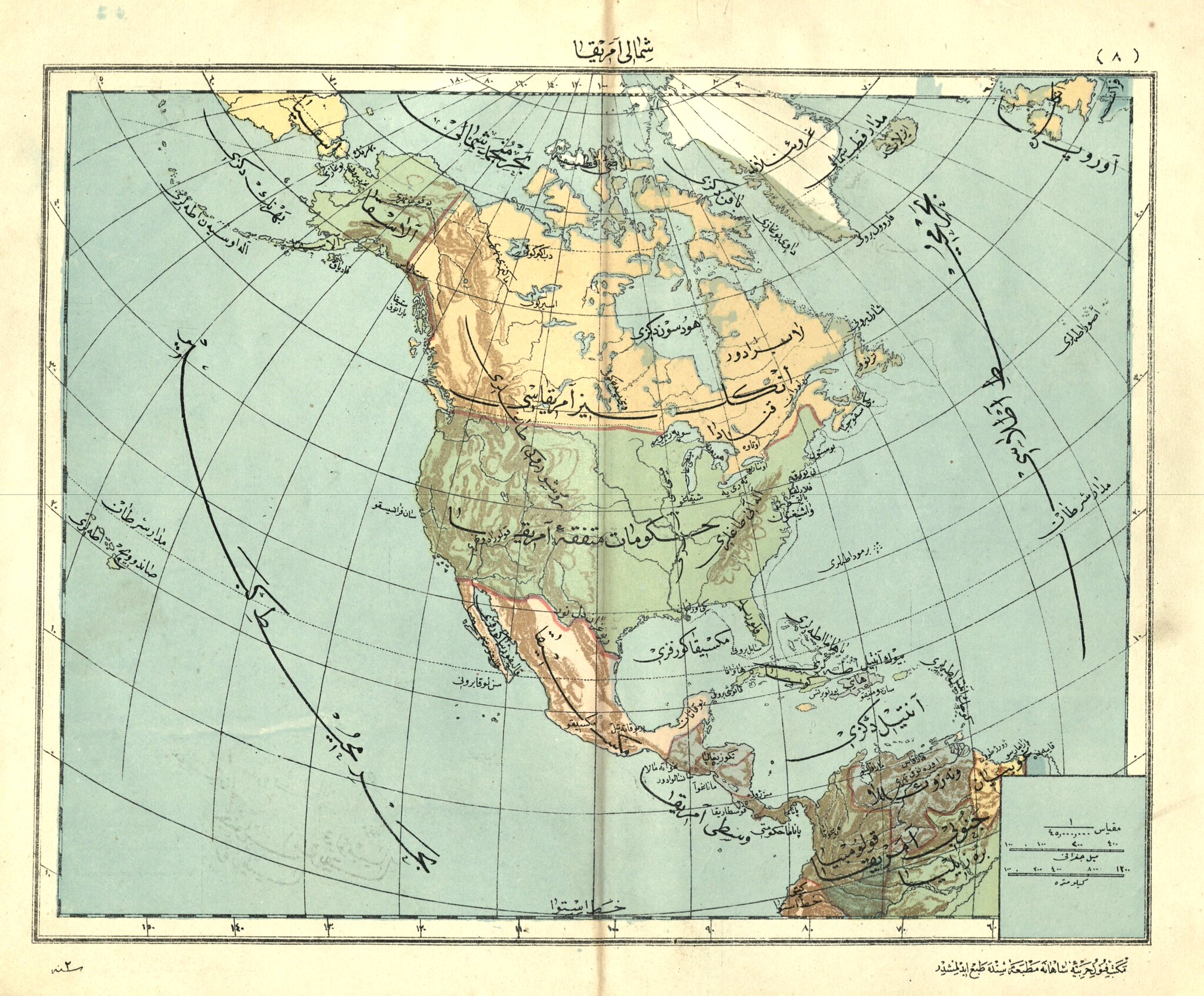

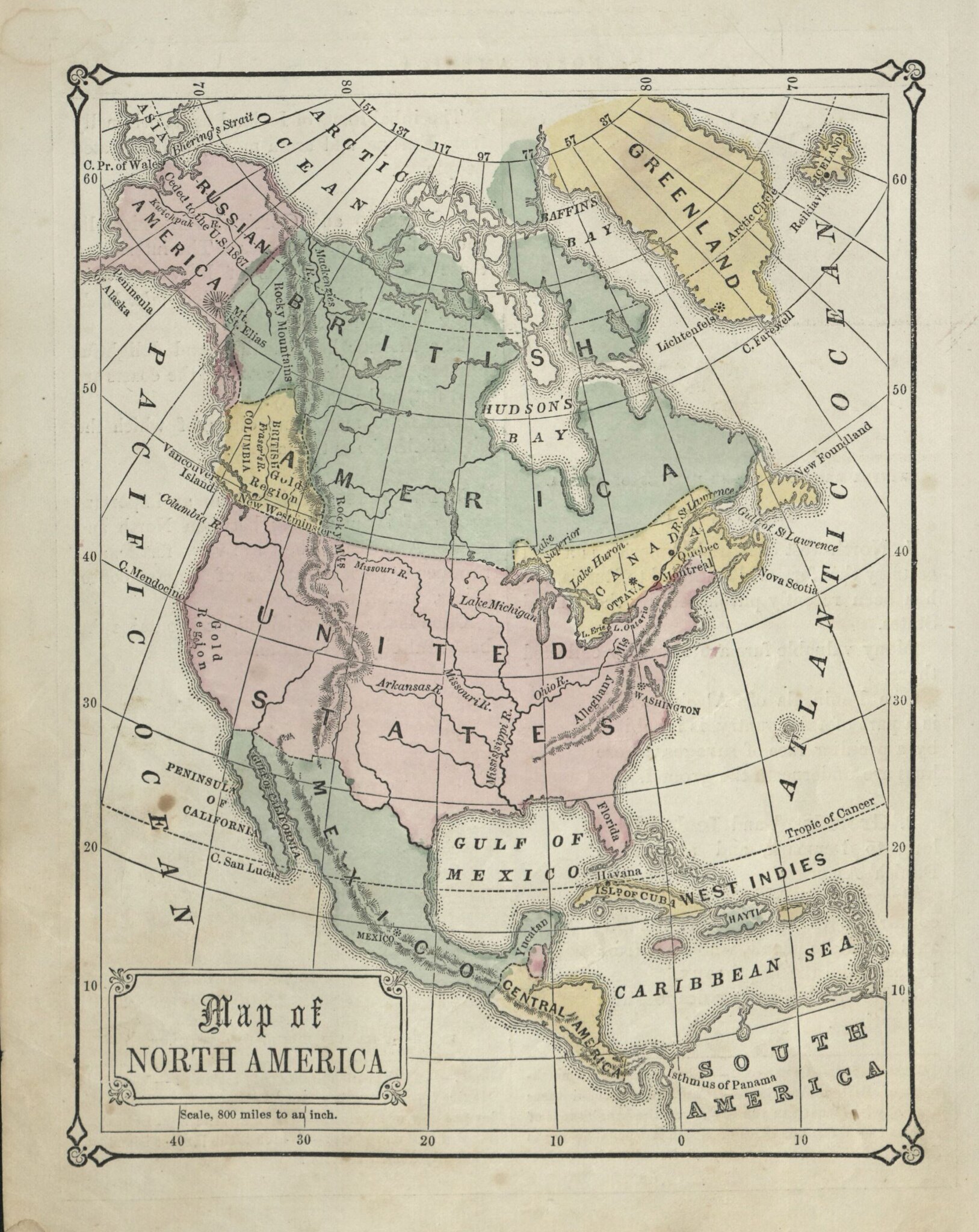

In is no secret that the French administration in Syria and Lebanon during the Mandate period sought to categorize the population and divide it along various ethnic and sectarian lines, and while this process did to some extent have origins in the Ottoman period, no colonial power had mastered the art of dividing the races quite like the French. In many ways, the sectarian orders in these countries--to the extent that they survive today--are a holdover form this important interwar period. The efforts to classify and govern the population resulted in the production of various breakdowns of the region that give an impression of precision and intense attention to local detail that belies the imperfection of these representations that have the power to mislead. This approach to map-making fit with the France's creation of ethnically-defined political units such as the Alawite State of Lattakia. In short, reader beware, taking the date reflected in this map at face value or using it to talk about the present would be ill-advised and anachronistic.

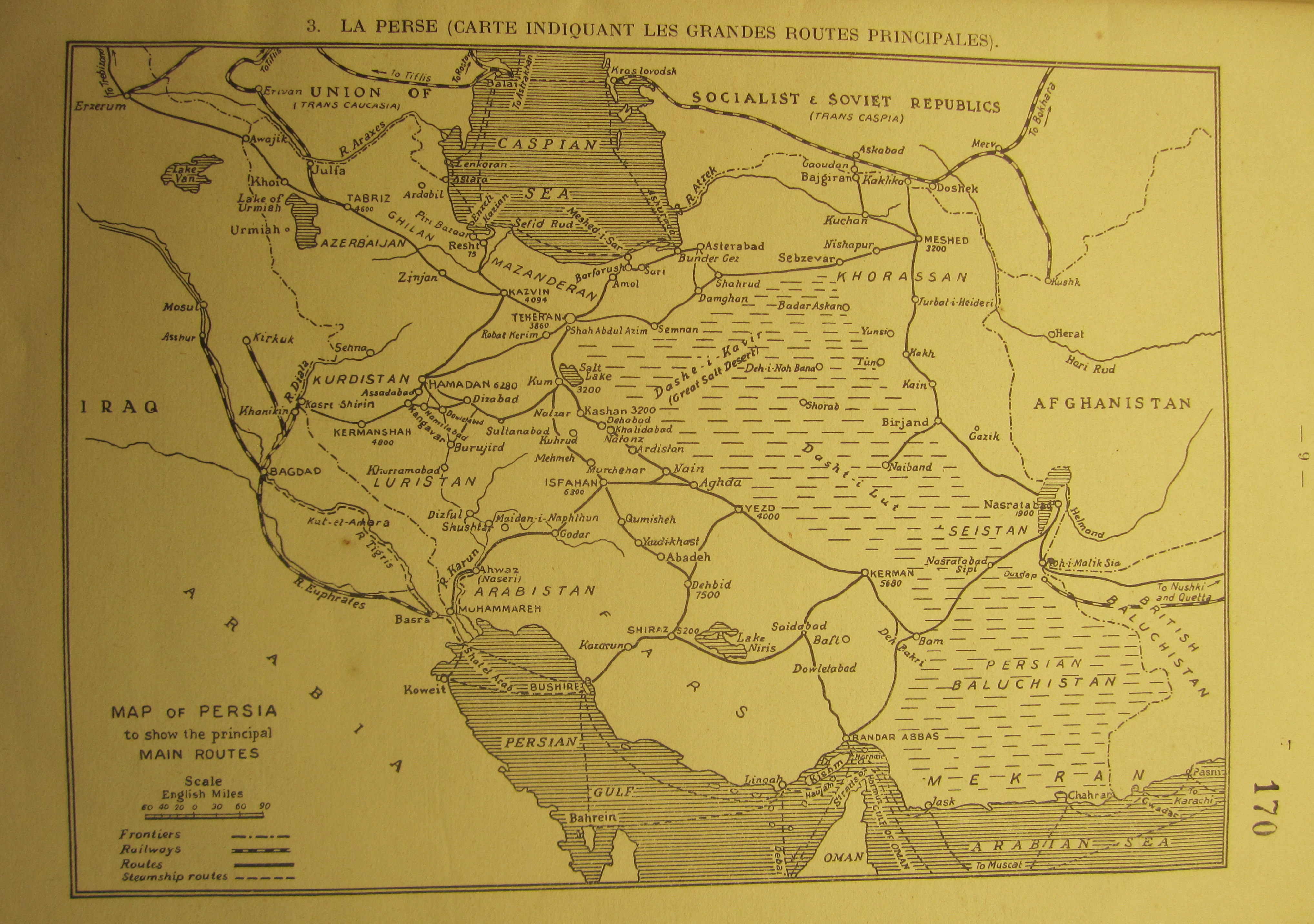

This map drafted by the Services Speciaux of the French Mandate dates to approximately 1935 (apologies for any flaws in the photographs taken with a small camera, in low light, and of a rather large map). It represents regions of the French Mandate in terms of the communities that predominated in each area as well as offering some information about the different tribal groups in Greater Syria and their patterns of movement. The key below displays roughly how the French administration divided the population (the seemingly repetitive designation of Turcoman and Turkméne may be an error, since the latter symbol does not seem to appear anywhere on the map).

While there is apparently great effort to include even the smallest concentrations of one group located in a zone dominated by the other, the construction of these zones obscures the fact that in many of them a large minority and in some cases perhaps a majority of the inhabitants would have been outside the dominant group determined and represented by the French. One such example might be the apparent assertion that the port of Alexandretta was far and away a majority Christian city. Essentially, regions are represented in a radically simplified fashion.

Likewise, the identities on this map are externally constructed; there is no guarantee that they conform to local understanding of identity and indeed, an ethnic community such as Circassians could just as easily chosen to prioritize their Sunni identification when defining themselves vis a vis their neighbors, just as Christians and Alawites might choose to prioritize an ethnic identity, namely the Arab one that appears nowhere on this map. This absence is by far more conspicuous than all the precise divisions on the map, because alongside the Sunni identity shared by many of the "non-Arab" ethnic groups in the above table, some form of Arab identity was the one with most overlap across these categories. Indeed, it was one that was already forming the basis of a national identity in Syria and Lebanon and would dominate the post-mandate politics of the former in particular. In the hyper-nationalist climate of the 1930s, it is telling that the French system continued to distinguish these groups by religious categories and subcategories. We have Muslims in shades of red, Christians in blue, what seems to be a group of questionable Muslims in yellow, and Turks (including Kurds) in green, giving the sense of an overly fragmented population very much in accord with a divide and rule strategy.

It is interesting to consider this map alongside analogous maps and reports from the brief occupation of Cilicia (1918-1922), a region centered on the city of Adana. There, French administrators produced numerous reports elaborating upon the various different "races" that made up the heterogeneous society in Cilicia (Sam Kaplan has written a very substantial article on this subject). These reports distinguished between various Muslim communities such as "Turks," "Arabs," "Kurds," "Circassians," and so forth, as well as the various religious communities that could be identified. Whereas Muslim subjects were counted in the same category under the Ottomans, the French sought to identify new categories. Of course, one could argue that the Ottomans had done the reverse, dividing various Christian communities while proclaiming a false unity of Muslim subjects for political reasons. Either way, the new French divisions in Cilicia served the purpose of ensuring that Armenians were represented on paper as the single largest group in the French Mandate of Cilicia, thereby bolstering French claims to govern there during the League of Nations period.

However important or unimportant the categories used in interwar ethnographic studies of the French Mandate were, there is also a case to be made that the continual usage of such categories in the administrative domain did encourage French subjects to identify within them. We see evidence of this in the emergent political order of Lebanon or the emergence of an Alawite identity in Syria, fostered by a French policy of recruiting and promoting Alawites within the army.

However important or unimportant the categories used in interwar ethnographic studies of the French Mandate were, there is also a case to be made that the continual usage of such categories in the administrative domain did encourage French subjects to identify within them. We see evidence of this in the emergent political order of Lebanon or the emergence of an Alawite identity in Syria, fostered by a French policy of recruiting and promoting Alawites within the army.

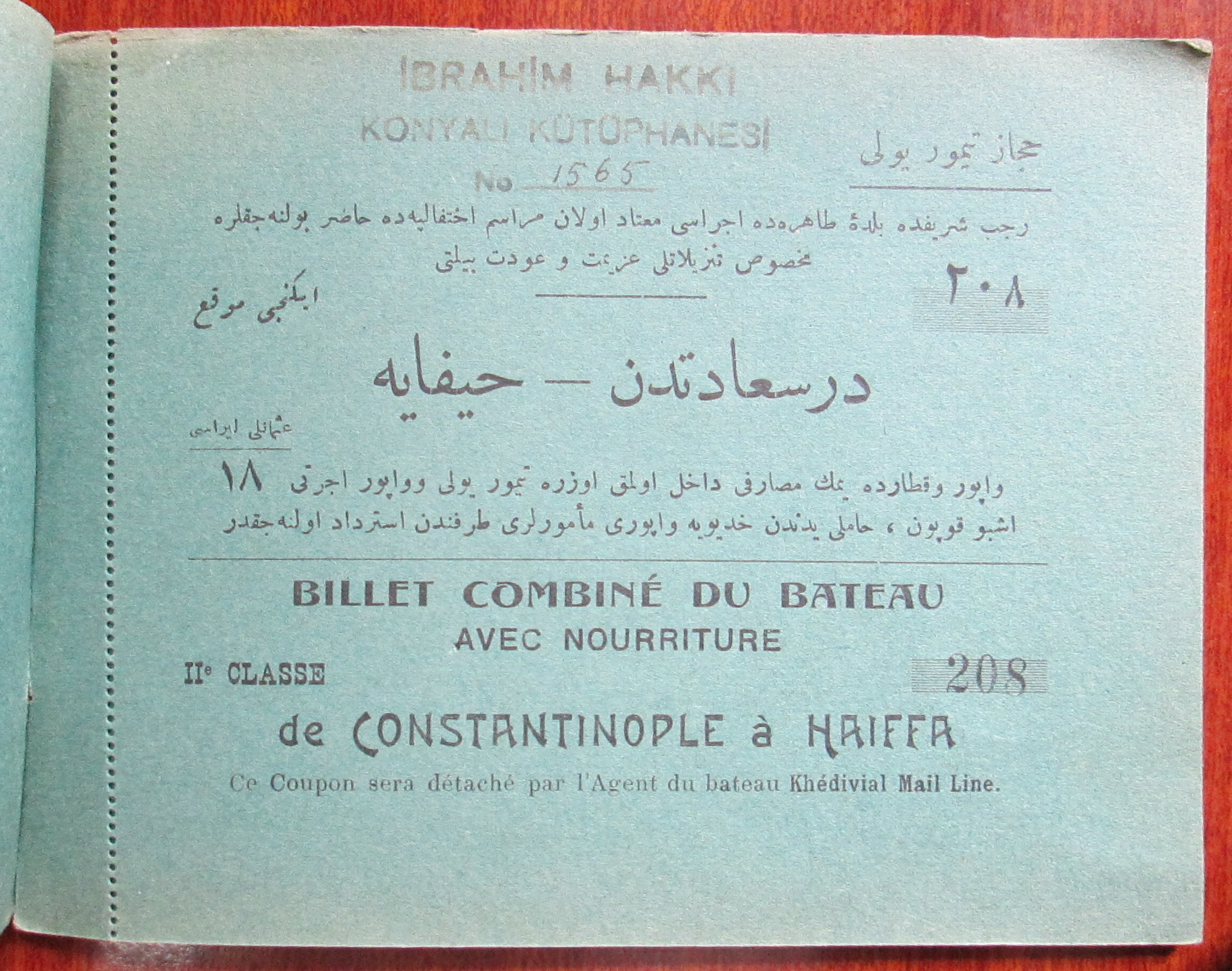

Just as these maps may give the false impression of simplicity in their breakdown, they were also not necessarily intended as perfect representations. Indeed, they were works in progress. In the case of this particular map, we happen to know from a letter (at right) requesting two minor revisions in the vicinity of Safita/Tripoli that amendments were continually made to such maps.

Likewise, the identities on this map are externally constructed; there is no guarantee that they conform to local understanding of identity and indeed, an ethnic community such as Circassians could just as easily chosen to prioritize their Sunni identification when defining themselves vis a vis their neighbors, just as Christians and Alawites might choose to prioritize an ethnic identity, namely the Arab one that appears nowhere on this map. This absence is by far more conspicuous than all the precise divisions on the map, because alongside the Sunni identity shared by many of the "non-Arab" ethnic groups in the above table, some form of Arab identity was the one with most overlap across these categories. Indeed, it was one that was already forming the basis of a national identity in Syria and Lebanon and would dominate the post-mandate politics of the former in particular. In the hyper-nationalist climate of the 1930s, it is telling that the French system continued to distinguish these groups by religious categories and subcategories. We have Muslims in shades of red, Christians in blue, what seems to be a group of questionable Muslims in yellow, and Turks (including Kurds) in green, giving the sense of an overly fragmented population very much in accord with a divide and rule strategy.

It is interesting to consider this map alongside analogous maps and reports from the brief occupation of Cilicia (1918-1922), a region centered on the city of Adana. There, French administrators produced numerous reports elaborating upon the various different "races" that made up the heterogeneous society in Cilicia (Sam Kaplan has written a very substantial article on this subject). These reports distinguished between various Muslim communities such as "Turks," "Arabs," "Kurds," "Circassians," and so forth, as well as the various religious communities that could be identified. Whereas Muslim subjects were counted in the same category under the Ottomans, the French sought to identify new categories. Of course, one could argue that the Ottomans had done the reverse, dividing various Christian communities while proclaiming a false unity of Muslim subjects for political reasons. Either way, the new French divisions in Cilicia served the purpose of ensuring that Armenians were represented on paper as the single largest group in the French Mandate of Cilicia, thereby bolstering French claims to govern there during the League of Nations period.

However important or unimportant the categories used in interwar ethnographic studies of the French Mandate were, there is also a case to be made that the continual usage of such categories in the administrative domain did encourage French subjects to identify within them. We see evidence of this in the emergent political order of Lebanon or the emergence of an Alawite identity in Syria, fostered by a French policy of recruiting and promoting Alawites within the army.

However important or unimportant the categories used in interwar ethnographic studies of the French Mandate were, there is also a case to be made that the continual usage of such categories in the administrative domain did encourage French subjects to identify within them. We see evidence of this in the emergent political order of Lebanon or the emergence of an Alawite identity in Syria, fostered by a French policy of recruiting and promoting Alawites within the army.Just as these maps may give the false impression of simplicity in their breakdown, they were also not necessarily intended as perfect representations. Indeed, they were works in progress. In the case of this particular map, we happen to know from a letter (at right) requesting two minor revisions in the vicinity of Safita/Tripoli that amendments were continually made to such maps.

Here are some close-ups of different areas:

|

| Mount Lebanon |

|

| Northern Syria |

|

| Jezireh/Eastern Syria |

Source: MAE-Nantes, 1SL/1/V 2129