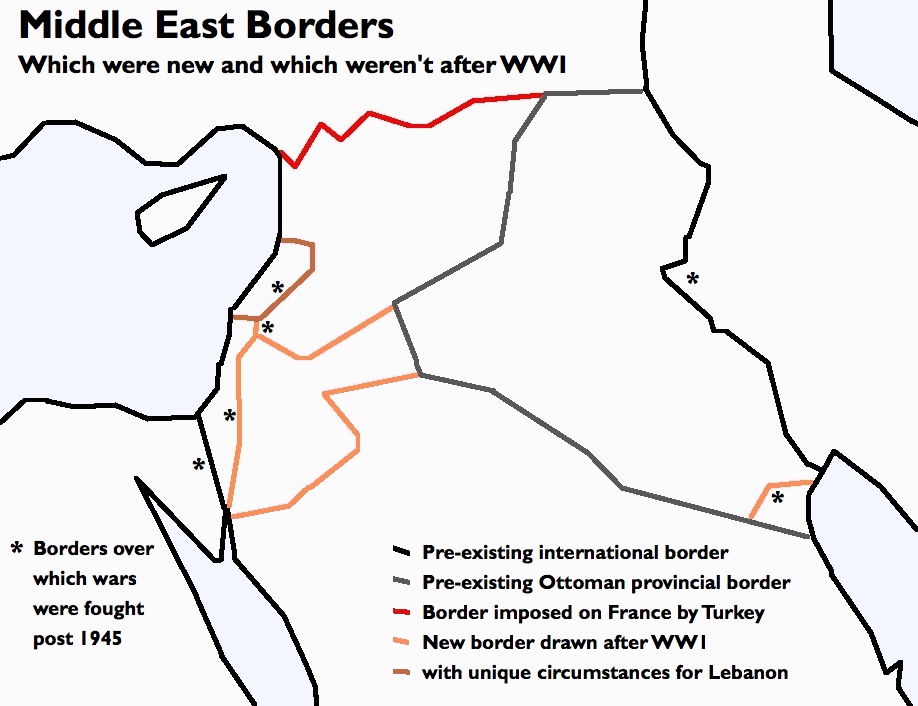

After posting all these beautiful maps of different Ottoman and Turkish cities I'm a little embarrassed to put up such an ugly one of my own, especially since I actually don't really think the complexities of Mandate-era border demarcation and state-formation can be mapped terribly effectively. But trying seems like an excellent way to think more deeply about what we really mean when we talk about "artificial" or "externally-imposed" borders in the Middle East. Which is, of course, something that I love talking about.

Among the first things to stand out is the exact demarcation of Iraq's Western border certainly was new in the mandate period. But, as its straightness suggests, it was drawn through a largely uninhabited region whose emptiness the Ottoman Empire had taken to be the division between Sham and Der Zor in the West and the Baghdad and Basra in the East.

Though the territory of Egypt was not officially independent in the 19th century, the border between Israel and Egypt today fits with boundary between Mehmet Ali's de facto territory and the remaining parts of the Ottoman Empire.

Kuwait's border, in turn, was drawn a few decades before world war one at the turn of the century when the British signed a treaty with an emir who had nominally been under the authority of the Basra governor before. This, of course, was one of Saddam Hussein's justifications for invading Kuwait, though he obviously never saw fit to criticize the British for their decision to join Basra and Mosul to Baghdad in the first place.

Similarly, the Turkish-Syrian border has caused considerable resentment among Syrian nationalists who blame France for giving Turkey the territory of Alexandretta (now Hatay) as part of a 1939 diplomatic deal. What they seldom mention is that if the issue had been left to the force of arms Turkey might have ended up with Aleppo too. Which is how the rest of the Turkish-Syrian border was formed following Turkish military victories in the war of independence.

Lebanon, whose loss is also resented by Syrian nationalists, has an even more complicated history. Parts of Mt. Lebanon had already been created as an autonomous, Christian, province in the 19th century under European pressure following the outbreak of "sectarian" violence in the 1840s and 1860s. In short the religious identities that were invoked, than militarized in the power vacuum that followed Mehmet Ali's occupation of the region created a situation whereby drawing political boundaries between Christians and Musliims seemed like the only way to maintain peace. Crucially, following World War One the French enlarged this territory, creating a stronger and more viable state for their Maronite allies by incorporating port cities like Beirut into an expanded Lebanese state.

Jordan, finally, is the most purely "artificial" state in the Middle East, made from leftover scraps of desert in part to give King Abdullah something to rule over, in part to help control beduoin raids on French Syria. It has also remains one of the most stable states in the entire region. While some early Zionists sought to create a state that encompassed all of the original Mandate of Palestine including the area that became Trans-Jordan, by 1948 most had realized that cooperating with King Abdullah could work out well for everyone. Or at least for the Zionists and King Abdullah, if not necessarily the Palestinians.

It is a little hard to know where to fit Israel into this picture. It seems safe to say that the problems that ensued from the formation of a Jewish state in the Middle East were never really about the borders. In fact, the UN partition plan would have given the new state of Israel the most exhaustively studied, carefully drawn borders of almost any state in the world. But the one thing Zionists and Arab nationalists alike could agree on was that these borders were completely unacceptable.