Amidst a number of centenary celebrations for the First World War I wanted to compile a list of the maps we've featured over the years that touch in one way or another on the experience and consequences of the war in Ottoman lands. These include maps that I hope can help illuminate the Ottoman Empire's motives in joining the war, as well as maps actually used in the conduct of the war itself. Equally interesting are the wealth of ethnographic and irredentist maps produced after the war to contest the political disposition of Ottoman lands. Finally, another set of maps deals with the commemoration of the war, maps made during the ensuing century to celebrate or mourn its consequences. As always, questions, comments, contributions and criticisms can be addressed to Nick Danforth or the individual contributors.

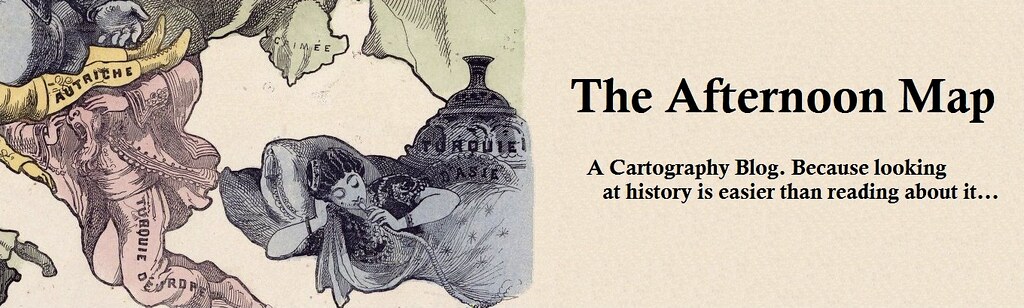

Intikam. Courtesy of the Atatürk Kitaplığı, this map is titled simply Intikam or Revenge. Published by the Rumeliya Muhacirin-i Islamiyesi Cemiyeti or Society of Muslim Refugees from Rumeliya, the map shows, in black, the part of the Ottoman Empire lost during the Balkan Wars from which these refugees fled. The region's most important cities, where many of these refugees had lived, appear in the small white circles.

German Asia Minor. This map, and its companion, first appeared as a supplement to Adolf Guyer-Zeller 1897 work Der Türkenherrschaft ende, or "The End of Turkish Occupation." Guyer-Zeller was a Swiss rail-road magnate, who, as these maps reveal, seemed keenly interested in the potential of German Imperialism to create to rail routes. From the Ottoman perspective, of course, maps like this offer another insight into how the empire found itself disastrously involved in World War One. If Intikam highlights the Empire's desire to avenge its territorial losses, this map, by contrast, highlights the fear of much more serious losses. Ottoman statesmen were conscious of the fact that even their allies were eager to carve up what was left of their territory. After decades of seeing maps like these, there was ample reason for Ottomans to suspect that if they sat out the war they would lose no matter who won. When the war broke out, the CUP leadership initially tried to delay their entry until the winner was clear, but ultimately decided, with some help from Enver Pasha, that neutrality was more dangerous than the risk of ending up firmly on the losing side. From a purely strategic perspective, betting on a German victory was hardly a foolish thing to do, and as anyone who plays backgammon knows, sometimes luck can make even a smart move end in disaster.

Though the Ottomans developed their own cartographic bureaucracy, they also relied heavily on maps made by others. In World War One, this meant that they often fought not only with maps provided by the Germans, but also maps made by the countries they were fighting against. In many cases, as can be seen, they amended these maps, drawing in new towns, re-labelling geographic features in Ottoman or providing elaborate keys to transliterate the names of these features.

1915 Ottoman Ethnographic map of the Middle East. The map, found by Zach Foster, comes from the Filastin Risalesi, an official 1915 publication of the Ottoman army intended to be used as an officer’s manual for the Palestine region. The key includes:

Maronite

Durzi (Druze)

Yahudi (Jews)

Arab

Suriyeli (from Syria)

Rum (Greek / Ottoman Greek)

Turk

Turkmen yahut Turk (Turkmen or Turks)

Ismaililer (Ismaili Shiites)

Mutawalli

Nusayri.

Another map, also from Zach Foster: "World War I saw the rapid spread of diseases in the Ottoman Empire. Soldiers who were frequently on the move between battlefronts became ideal carriers for many types of microbes, while mass deportations like those of the Armenian genocide also contributed to outbreaks. The war drove up the price of soap and made it prohibitively expensive for many across the region, further hastening the spread of diseases. And, as famine and starvation began to spread across Syria, especially Lebanon, emaciated bodies became particularly vulnerable to diseases, especially Typhus, known by some as ‘hunger typhus’ for its tenacity to attack the malnourished. Fever, TB and Cholera also spread rapidly during the war. And so the Ottomans undertake a campaign to create disinfection stations across the region, as seen above in this map of Mount Lebanon produced in (roughly) 1915. The red crescents show canteens (matam mahalleri gösterir); the dark crescents represent disinfection stations (tebhir istansyonlar gösterir); the half-red half-dark crescents indicate canteens that include a disinfection center (matam mahallerinde tebhir istasyonun mevcudunu gösterir). The disinfection centers were established under a new law called The Regulation for Communicable Diseases ( Nizam-i Emraz-i Sariye), as Dr. Tanielian has shown, which required all cases of diseases to be reported within 24 hours to the local health authorities. Although it is unclear what kind of disinfection took place at the centers – probably a combination of treatment and quarantine – this was a clear attempt to expand the role of the state in monitoring and controlling the spread of diseases."

Ethnic maps that were made for propaganda purposes during the war also helped set the stage for the intense debate over remaking the region at the war's end. This US made map showing "Subject Nationalities of the German Alliance (larger version here) offers a nice contrast with it's German counterpart here. The American map shows the subjects of the Axis powers, for whom Woodrow Wilson sought self determination. The second shows the overseas colonies of the Entente powers. To make a long story short, the Entente won, so their enemies' subjects in Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the Middle East were granted independence (well, with the exception of the ones in the Middle East). The subjects of the entente would have to wait until after World War Two.

Ethnic maps that were made for propaganda purposes during the war also helped set the stage for the intense debate over remaking the region at the war's end. This US made map showing "Subject Nationalities of the German Alliance (larger version here) offers a nice contrast with it's German counterpart here. The American map shows the subjects of the Axis powers, for whom Woodrow Wilson sought self determination. The second shows the overseas colonies of the Entente powers. To make a long story short, the Entente won, so their enemies' subjects in Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the Middle East were granted independence (well, with the exception of the ones in the Middle East). The subjects of the entente would have to wait until after World War Two.

This images come from a remarkable collection of maps made using 1917 census data purporting to show the ethnic composition of the territory that the Ottoman Empire still hoped to hold on to after World War One. It is written in French, suggesting that it was intended for an international audience, suitable to serve as a visual aid at a European peace conference. (If anyone knows more about M. Salih, who made this particular set of maps, I'd be curious to know. They appeared in the IRCICA library, which has an amazing maps but little information about the source of their collection). Woodrow Wilson's emphasis on national self-determination gave many people - members of ethnic minorities but also in many cases leaders of non-Western states like Turkey - hope that any post-war settlement would recognize their political and territorial aspirations. These hopes were based both on an optimistic assessment of the role Wilson's Fourteen Points would play in peace negotiations as well as generally optimistic demographic readings of the region inhabited by members of a particular nation. In this context, the production of maps like these were part of the rhetorical arsenal of every state and minority group aspiring to statehood in the immediate post-war era.

The King-Crane Commission: An interactive map with some highlights from the King-Crane Commission Report prepared to accompany an article but possibly useful for students as well.

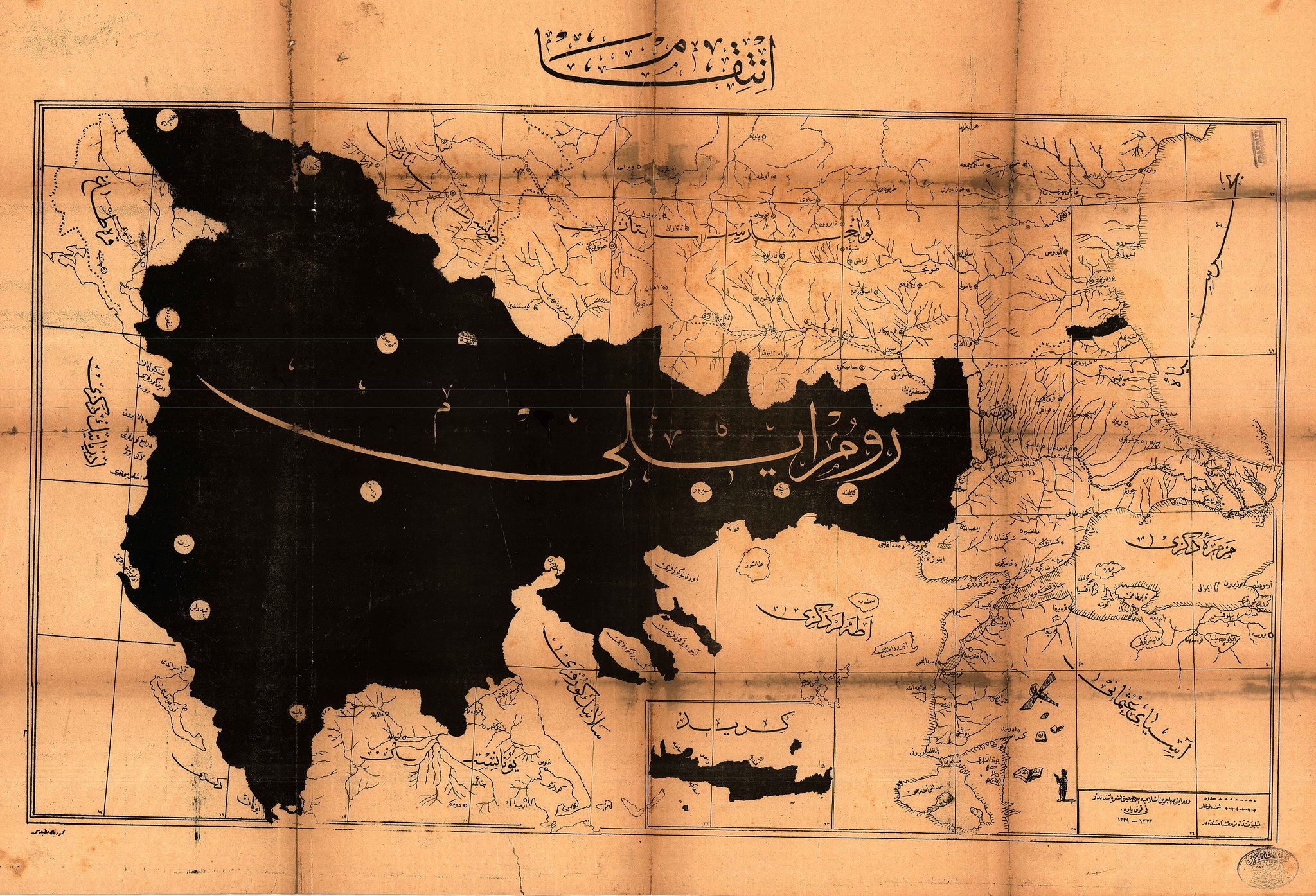

The New Assyria Sent in by Benjamin Trigona-Harany, who says: I've always liked this map because it signals that the adoption of a shared ethnic Assyrian identity by the Chaldeans, Nestorians and Süryani was in full swing - not to mention showing their charmingly optimistic borders for a future Assyrian state." It makes a nice addition to some of the better known plans from the post war era, including Megali Greece, Greater Albania, and Palestine

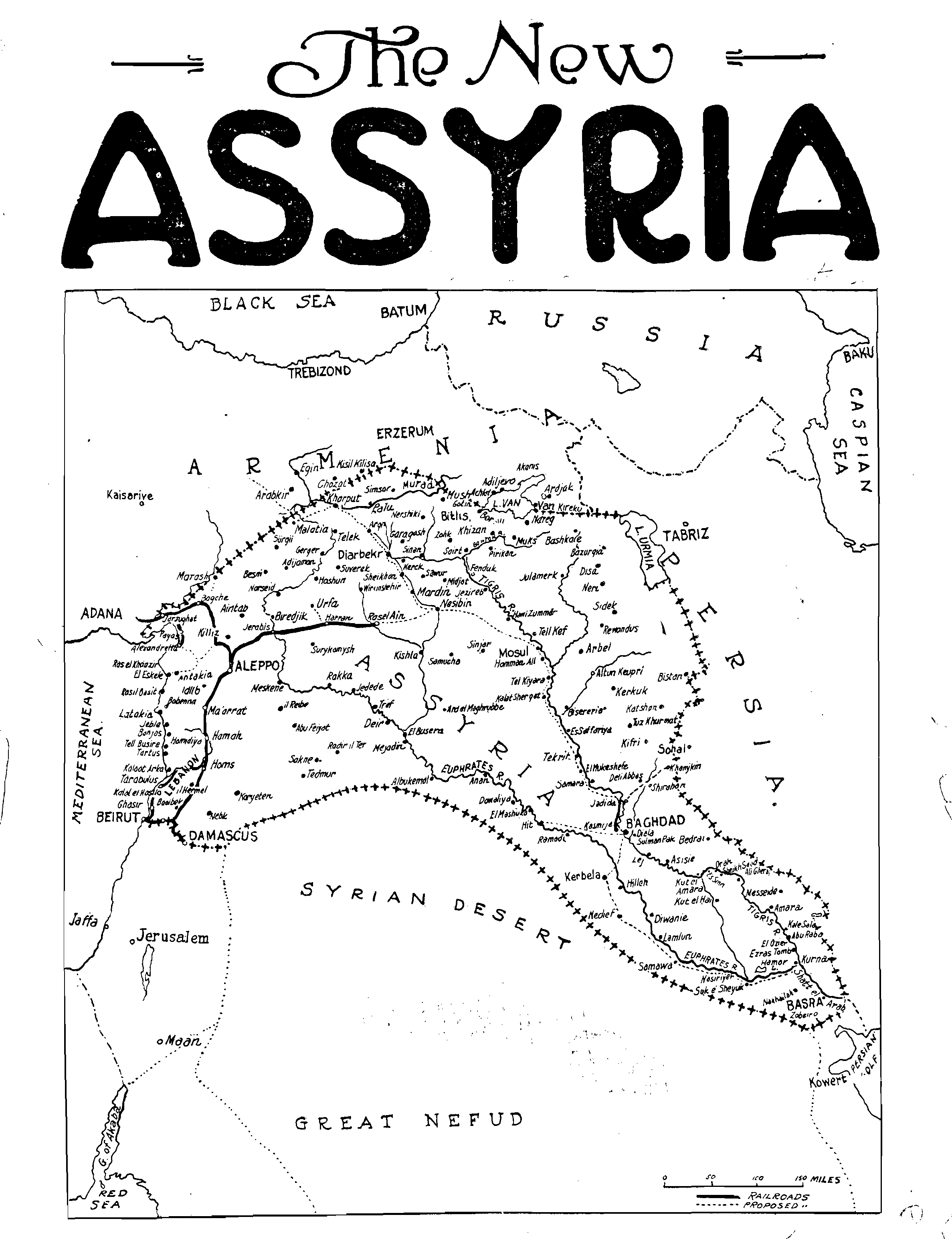

The Syrian Kingdom One of images from a pamphlet titled Dhikrá istiqlāl Sūriyā also sent along to us by Zach Foster. The first shows Faisal, best known as king of Iraq, and the second shows the territory he claimed in 1920 as part of his short-lived Arab Kingdom based in Damascus. Faysal ruled Damascus beginning in October 1918 and ending in July 1920, though he only declared himself King four months before the end. The French army refused to allow the creation of Faisal's Syrian kingdom, defeating a small contingent of Faisal's forces at the battle of Mysalun. Faisal was given Iraq as a consolation prize by the British, which his successors ruled until 1958 when they were ousted by a coup. Had Faisal's dream of a free Arab kingdom become reality, the Middle East might have been spared many of the conflicts it endured over the past century. Or maybe it still would have seen conflicts between the Arab Kingdom and its Christian minority, Kurdish minority and Zionist minority. Or between the Arab Kingdom and the Republic of Turkey. Or Iraq. Or Egypt. As Zach points out, even during his glorious short lived period of rule he struggled to convince others outside of damascus to subject themselves to his rule. James Gelvin's Divided Loyalties (p. 30) even reports that delegation of Aleppan notables used the occasion of Faisal's coronation to demand independence for their region. Suffice it to say this did not bode well for his future prospects of ruling all of Syria, let alone Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine.

French Ethnographic Map of the Levant. From Chris Gratien: a French map from roughly 1935 reflecting the colonial view of a religiously and ethnically diverse region united under the mandates of Lebanon and Syria. It gives the sense of a highly fragmented and segregated society, reflecting in no doubt policies of French rule that fostered divisions between the region's different communities. The glaring omission from the numerous markers of identity displayed on this map is the category of Arab, a long-standing entholinguistic category that would have encompassed a majority of people represented by this map. Indeed, the growing political purchase of Arab nationalism during this period made the French so uncomfortable with it as a category in the first place. (Source: CADN 1SL/1/V 2129)

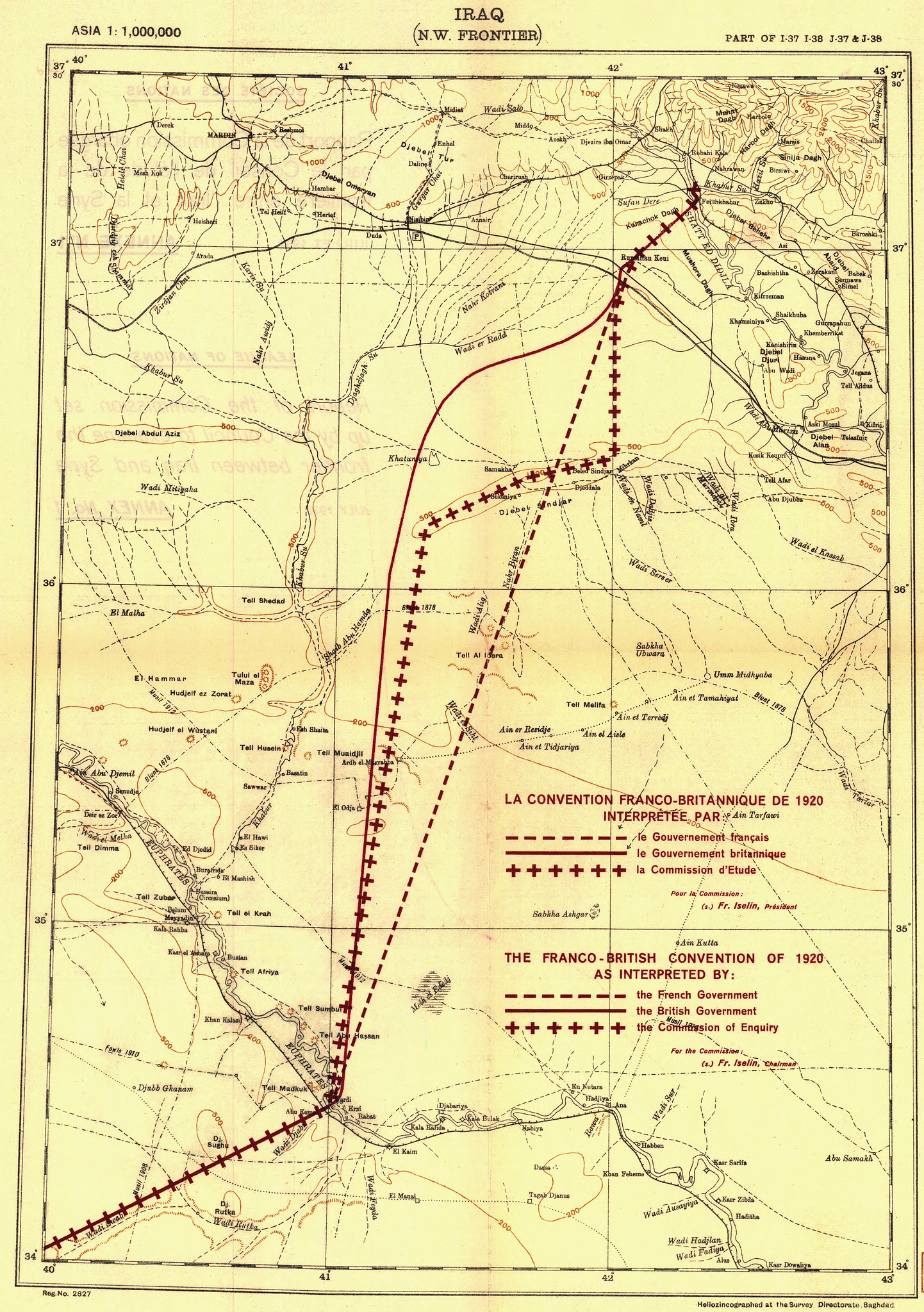

The Iraqi Syrian Border. With the rise of ISIS, we've heard a lot about the artificiality of Middle Eastern borders, and there's obviously been a particular focus on the non-overrun border between Syria and Iraq. This map offers a nice reminder that the British and French themselves apparently cared so little about the stretch of desert this border went through that they actually left its delimitation up to a League of Nations committee in the 30s sometime.

This is a detail from a map of Istanbul and the straits printed on a silk handkerchief and given to allied soldiers as a rather premature commemoration of their victorious Gallipoli campaign. On the bottom left of the map are the words "To Constantinople" at the mouth of the Dardenelles, while the silouhette of the city stands as the ultimate objective in the top right. On the corners are sheilds with the Australian and New Zealand flags and the words "well done" along with a the one to the left titled "Eclipse of the Star and Crescent." There's no evidence the British actually had a flag like this in mind for conquered Ottoman territory, although it certainly does a good job of getting their general intentions across. The original handkerchief is on display at the Iskenderun Deniz Muzesi, which is definitely worth a visit if you're in Iskenderun.

After the war, of course, the Republic of Turkey celebrated Gallipoli in a more traditional fashion, including images like this. Combining aspects of a map and a panorama view of the battle itself, this piece might be of more interest for its aesthetic qualities (as well as the transliterations of some of the British boat names) than as a historical document.

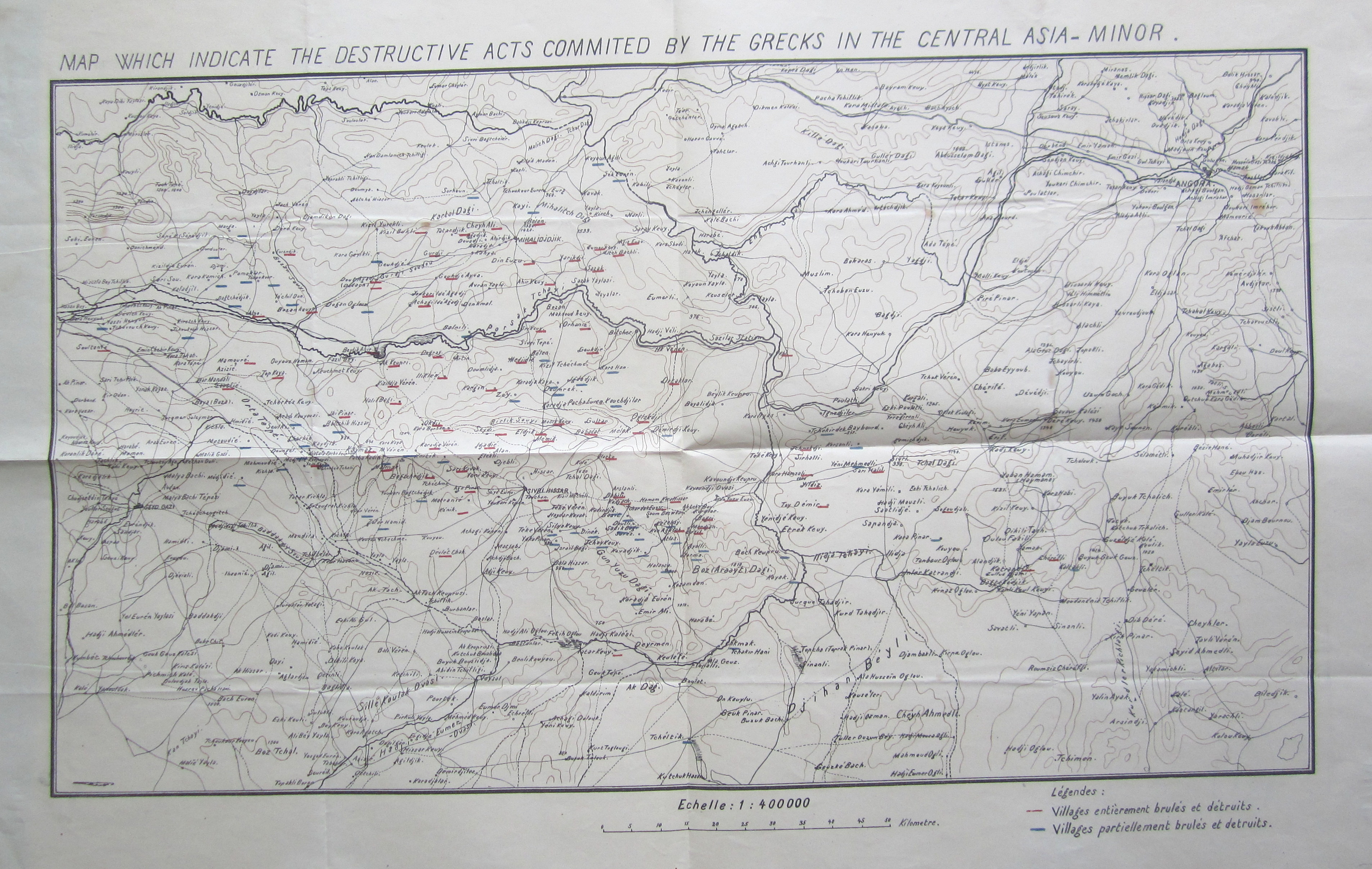

What the Greeks Destroyed. Courtesy of Chris Gratien: "These maps appeared in the files of the education ministry, meaning that they were intended for a certain didactic function. The above map, which is available in numerous copies both English and Ottoman in different boxes from the national struggle period attempts to show village by village areas destroyed or partially destroyed by the Greek army underlined in red and blue respectively. I compared the numerous copies of the map that I found and all are consistent in their representation of which villages had been destroyed and to what extent. That it survives in so many copies and that it was published in both English and Ottoman Turkish emphasizes how the nationalist narrative was being deployed through maps and education in the very moment that these events were unfolding."

Map of the Armenian town of Hadjin. Again from Chris Gratien: "Members of the Armenian diaspora communities conscious of the fact that their natal villages might someday be wiped from the historical memory sought to compile information about the history and social life of towns such as Hadjin in exhaustive histories usually composed in Armenian. One such work about Hadjin was published at a fairly early date in 1942, just two decades after the French withdrawal, meaning that many who had experienced the town as adults were able to contribute. Only a few copies of The Complete History of Hadjin were published, most of which were in the possession of contributors, donors, and families from the Hadjintsi community. Some eventually made their way into university libraries. These hand-drawn maps (composed in Los Angeles during the 1940s) are scanned from one such copy.

The Turkish government's efforts to destroy the memory of Anatolia's Armenian population are both furthered and undermined by the widespread fascination with treasure hunting in rural Turkey. As discussed here, many people in southeastern Turkey are convinced that treasure lies buried in the foundations of ruined Armenian churches and monasteries. In searching for it, they inevitably destroy these monuments further, but also re-enforce the presence of the land's former inhabitants in popular memory.

Not a map, but a fantastic obituary of Lawrence of Arabia that appeared in the satirical paper Akbaba at the time of his death. Some highlights:

Istanbul is famous for its beauty, Ankara its will; Paris its liveliness, Viena its operas, Switzerland its Sanatoriums and England is famous for Lawrence.

In the deserts during the Great War the Turkish army's most feared microbe was him.

In Lawrence's death the world's gain is as great as England's loss. Now it is more possible for nations to love each other and work together for peace.

Lawrence's death. As with any great joy it isn't easy to believe the good news.

If Lawrence is really dead... in that case people face a new fear: the fear of the hereafter.

An early cold war propaganda map showing Turkey as part of the Northern Tier, surrounded by a menacing sea of red. I think this map offers a partial rebuke to our tendency to see the experience of World War One and the "Sevres Syndrome" as the source of all Turkey's modern day militarism and nationalist paranoia. Yes, Turkey emerged from World War One, not just the War for Independence but the CUP period as well, with a political culture marked by these phenomenon. But so did most of the world. In fact, compared to some of the European countries that embraced fascism, Turkey was less militarized and less intensely xenophobic in the Republican period. And to suggest that these impulses were waiting to erupt just below the surface, kept in check only by Ataturk's personal charisma, really does seem to ignore the contingency of history. I would argue that the experience of the Cold War, culminating in the 1980 coup, did more to enshrine these impulses in modern turkish political culture than did the social and political climate of Turkey's founding. In connecting the dots directly from 1919 to the present, it's easy to forget that Turkey spent almost a half century regionally isolated by Cold War geopolitics. There was the Soviet Union was to the North and East, Warsaw Pact Bulgaria to the West and the Soviet-aligned states of Iraq and Syria to the South. Too often now discussions of the Sevres Syndrome imply it's merely an outdated bit of paranoia that was kept alive for a hundred years by the cynically authoritarian Kemalist state. But other things happened during this time, and their impact shouldn't be overlooked.

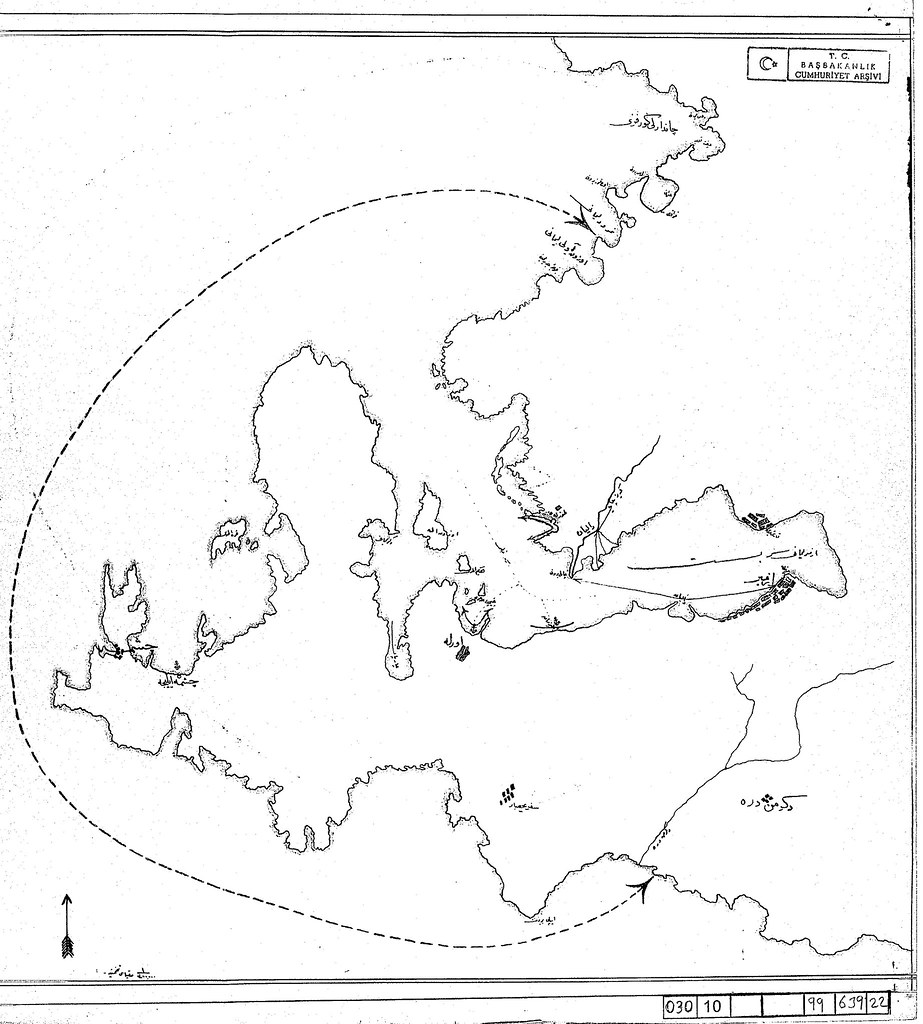

This is not, of course, to deny that the war's negative legacy in these regards. An example can be found in this map, showing the area off limits to non-Muslims and foreigners in the early years of the Republic. It is a telling illustration of the tension that existed between the government's insistence that all Turkish citizens were Turks regardless of their religion or race and an alternative conception of national identity in which the only real Turks were Turkish-speaking Sunni Muslims. The accompanying document, also from the Cumhuriyet Arsivi, lists exceptions to this prohibition, including travelers on ferries going into or out of the city, passengers on organized tours and workers on commercial craft who did not disembark.

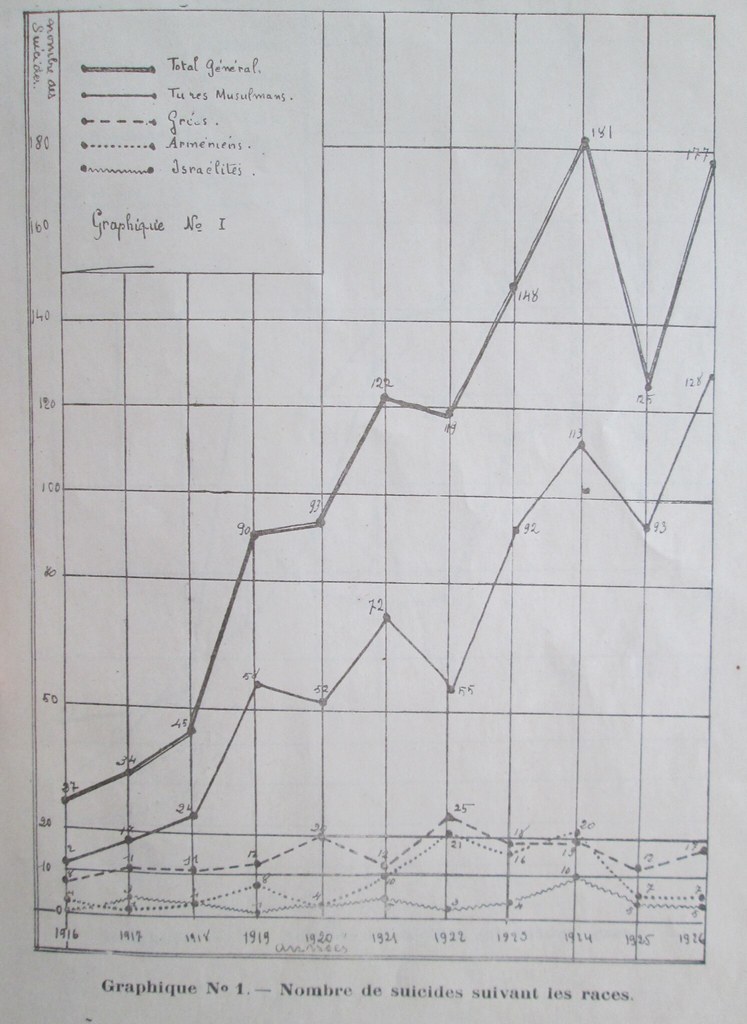

To end on a more somber non-cartographic note: Between 1916 And 1926, Istanbul’s Muslim residents – male and female, rich and poor -- began killing themselves at a quickly rising rate. Following a decade of fighting – the Balkan Wars, World War One, and the ensuing Greek-Turkish conflict – statistics published at the time show a jump in the number of documented suicides in all of the city's districts. It is a tragedy whose specific Turkish dimension has not been adequately discussed in the growing body of excellent work on the Ottoman experience of the Great War.

Finally, anyone interested in reading more deeply on the topics raised by these maps should check out the Ottoman History Podcast's World War One reading list, prepared by Heather Hughes:

World War I Reading List

Lead-Up

Intikam. Courtesy of the Atatürk Kitaplığı, this map is titled simply Intikam or Revenge. Published by the Rumeliya Muhacirin-i Islamiyesi Cemiyeti or Society of Muslim Refugees from Rumeliya, the map shows, in black, the part of the Ottoman Empire lost during the Balkan Wars from which these refugees fled. The region's most important cities, where many of these refugees had lived, appear in the small white circles.

German Asia Minor. This map, and its companion, first appeared as a supplement to Adolf Guyer-Zeller 1897 work Der Türkenherrschaft ende, or "The End of Turkish Occupation." Guyer-Zeller was a Swiss rail-road magnate, who, as these maps reveal, seemed keenly interested in the potential of German Imperialism to create to rail routes. From the Ottoman perspective, of course, maps like this offer another insight into how the empire found itself disastrously involved in World War One. If Intikam highlights the Empire's desire to avenge its territorial losses, this map, by contrast, highlights the fear of much more serious losses. Ottoman statesmen were conscious of the fact that even their allies were eager to carve up what was left of their territory. After decades of seeing maps like these, there was ample reason for Ottomans to suspect that if they sat out the war they would lose no matter who won. When the war broke out, the CUP leadership initially tried to delay their entry until the winner was clear, but ultimately decided, with some help from Enver Pasha, that neutrality was more dangerous than the risk of ending up firmly on the losing side. From a purely strategic perspective, betting on a German victory was hardly a foolish thing to do, and as anyone who plays backgammon knows, sometimes luck can make even a smart move end in disaster.

Mapping During the War

Though the Ottomans developed their own cartographic bureaucracy, they also relied heavily on maps made by others. In World War One, this meant that they often fought not only with maps provided by the Germans, but also maps made by the countries they were fighting against. In many cases, as can be seen, they amended these maps, drawing in new towns, re-labelling geographic features in Ottoman or providing elaborate keys to transliterate the names of these features.

1915 Ottoman Ethnographic map of the Middle East. The map, found by Zach Foster, comes from the Filastin Risalesi, an official 1915 publication of the Ottoman army intended to be used as an officer’s manual for the Palestine region. The key includes:

Maronite

Durzi (Druze)

Yahudi (Jews)

Arab

Suriyeli (from Syria)

Rum (Greek / Ottoman Greek)

Turk

Turkmen yahut Turk (Turkmen or Turks)

Ismaililer (Ismaili Shiites)

Mutawalli

Nusayri.

Another map, also from Zach Foster: "World War I saw the rapid spread of diseases in the Ottoman Empire. Soldiers who were frequently on the move between battlefronts became ideal carriers for many types of microbes, while mass deportations like those of the Armenian genocide also contributed to outbreaks. The war drove up the price of soap and made it prohibitively expensive for many across the region, further hastening the spread of diseases. And, as famine and starvation began to spread across Syria, especially Lebanon, emaciated bodies became particularly vulnerable to diseases, especially Typhus, known by some as ‘hunger typhus’ for its tenacity to attack the malnourished. Fever, TB and Cholera also spread rapidly during the war. And so the Ottomans undertake a campaign to create disinfection stations across the region, as seen above in this map of Mount Lebanon produced in (roughly) 1915. The red crescents show canteens (matam mahalleri gösterir); the dark crescents represent disinfection stations (tebhir istansyonlar gösterir); the half-red half-dark crescents indicate canteens that include a disinfection center (matam mahallerinde tebhir istasyonun mevcudunu gösterir). The disinfection centers were established under a new law called The Regulation for Communicable Diseases ( Nizam-i Emraz-i Sariye), as Dr. Tanielian has shown, which required all cases of diseases to be reported within 24 hours to the local health authorities. Although it is unclear what kind of disinfection took place at the centers – probably a combination of treatment and quarantine – this was a clear attempt to expand the role of the state in monitoring and controlling the spread of diseases."

Ethnic maps that were made for propaganda purposes during the war also helped set the stage for the intense debate over remaking the region at the war's end. This US made map showing "Subject Nationalities of the German Alliance (larger version here) offers a nice contrast with it's German counterpart here. The American map shows the subjects of the Axis powers, for whom Woodrow Wilson sought self determination. The second shows the overseas colonies of the Entente powers. To make a long story short, the Entente won, so their enemies' subjects in Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the Middle East were granted independence (well, with the exception of the ones in the Middle East). The subjects of the entente would have to wait until after World War Two.

Ethnic maps that were made for propaganda purposes during the war also helped set the stage for the intense debate over remaking the region at the war's end. This US made map showing "Subject Nationalities of the German Alliance (larger version here) offers a nice contrast with it's German counterpart here. The American map shows the subjects of the Axis powers, for whom Woodrow Wilson sought self determination. The second shows the overseas colonies of the Entente powers. To make a long story short, the Entente won, so their enemies' subjects in Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the Middle East were granted independence (well, with the exception of the ones in the Middle East). The subjects of the entente would have to wait until after World War Two.

Post-War Planning

This images come from a remarkable collection of maps made using 1917 census data purporting to show the ethnic composition of the territory that the Ottoman Empire still hoped to hold on to after World War One. It is written in French, suggesting that it was intended for an international audience, suitable to serve as a visual aid at a European peace conference. (If anyone knows more about M. Salih, who made this particular set of maps, I'd be curious to know. They appeared in the IRCICA library, which has an amazing maps but little information about the source of their collection). Woodrow Wilson's emphasis on national self-determination gave many people - members of ethnic minorities but also in many cases leaders of non-Western states like Turkey - hope that any post-war settlement would recognize their political and territorial aspirations. These hopes were based both on an optimistic assessment of the role Wilson's Fourteen Points would play in peace negotiations as well as generally optimistic demographic readings of the region inhabited by members of a particular nation. In this context, the production of maps like these were part of the rhetorical arsenal of every state and minority group aspiring to statehood in the immediate post-war era.

The King-Crane Commission: An interactive map with some highlights from the King-Crane Commission Report prepared to accompany an article but possibly useful for students as well.

The New Assyria Sent in by Benjamin Trigona-Harany, who says: I've always liked this map because it signals that the adoption of a shared ethnic Assyrian identity by the Chaldeans, Nestorians and Süryani was in full swing - not to mention showing their charmingly optimistic borders for a future Assyrian state." It makes a nice addition to some of the better known plans from the post war era, including Megali Greece, Greater Albania, and Palestine

The Syrian Kingdom One of images from a pamphlet titled Dhikrá istiqlāl Sūriyā also sent along to us by Zach Foster. The first shows Faisal, best known as king of Iraq, and the second shows the territory he claimed in 1920 as part of his short-lived Arab Kingdom based in Damascus. Faysal ruled Damascus beginning in October 1918 and ending in July 1920, though he only declared himself King four months before the end. The French army refused to allow the creation of Faisal's Syrian kingdom, defeating a small contingent of Faisal's forces at the battle of Mysalun. Faisal was given Iraq as a consolation prize by the British, which his successors ruled until 1958 when they were ousted by a coup. Had Faisal's dream of a free Arab kingdom become reality, the Middle East might have been spared many of the conflicts it endured over the past century. Or maybe it still would have seen conflicts between the Arab Kingdom and its Christian minority, Kurdish minority and Zionist minority. Or between the Arab Kingdom and the Republic of Turkey. Or Iraq. Or Egypt. As Zach points out, even during his glorious short lived period of rule he struggled to convince others outside of damascus to subject themselves to his rule. James Gelvin's Divided Loyalties (p. 30) even reports that delegation of Aleppan notables used the occasion of Faisal's coronation to demand independence for their region. Suffice it to say this did not bode well for his future prospects of ruling all of Syria, let alone Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine.

French Ethnographic Map of the Levant. From Chris Gratien: a French map from roughly 1935 reflecting the colonial view of a religiously and ethnically diverse region united under the mandates of Lebanon and Syria. It gives the sense of a highly fragmented and segregated society, reflecting in no doubt policies of French rule that fostered divisions between the region's different communities. The glaring omission from the numerous markers of identity displayed on this map is the category of Arab, a long-standing entholinguistic category that would have encompassed a majority of people represented by this map. Indeed, the growing political purchase of Arab nationalism during this period made the French so uncomfortable with it as a category in the first place. (Source: CADN 1SL/1/V 2129)

The Iraqi Syrian Border. With the rise of ISIS, we've heard a lot about the artificiality of Middle Eastern borders, and there's obviously been a particular focus on the non-overrun border between Syria and Iraq. This map offers a nice reminder that the British and French themselves apparently cared so little about the stretch of desert this border went through that they actually left its delimitation up to a League of Nations committee in the 30s sometime.

Cartographic Commemoration

This is a detail from a map of Istanbul and the straits printed on a silk handkerchief and given to allied soldiers as a rather premature commemoration of their victorious Gallipoli campaign. On the bottom left of the map are the words "To Constantinople" at the mouth of the Dardenelles, while the silouhette of the city stands as the ultimate objective in the top right. On the corners are sheilds with the Australian and New Zealand flags and the words "well done" along with a the one to the left titled "Eclipse of the Star and Crescent." There's no evidence the British actually had a flag like this in mind for conquered Ottoman territory, although it certainly does a good job of getting their general intentions across. The original handkerchief is on display at the Iskenderun Deniz Muzesi, which is definitely worth a visit if you're in Iskenderun.

After the war, of course, the Republic of Turkey celebrated Gallipoli in a more traditional fashion, including images like this. Combining aspects of a map and a panorama view of the battle itself, this piece might be of more interest for its aesthetic qualities (as well as the transliterations of some of the British boat names) than as a historical document.

What the Greeks Destroyed. Courtesy of Chris Gratien: "These maps appeared in the files of the education ministry, meaning that they were intended for a certain didactic function. The above map, which is available in numerous copies both English and Ottoman in different boxes from the national struggle period attempts to show village by village areas destroyed or partially destroyed by the Greek army underlined in red and blue respectively. I compared the numerous copies of the map that I found and all are consistent in their representation of which villages had been destroyed and to what extent. That it survives in so many copies and that it was published in both English and Ottoman Turkish emphasizes how the nationalist narrative was being deployed through maps and education in the very moment that these events were unfolding."

Map of the Armenian town of Hadjin. Again from Chris Gratien: "Members of the Armenian diaspora communities conscious of the fact that their natal villages might someday be wiped from the historical memory sought to compile information about the history and social life of towns such as Hadjin in exhaustive histories usually composed in Armenian. One such work about Hadjin was published at a fairly early date in 1942, just two decades after the French withdrawal, meaning that many who had experienced the town as adults were able to contribute. Only a few copies of The Complete History of Hadjin were published, most of which were in the possession of contributors, donors, and families from the Hadjintsi community. Some eventually made their way into university libraries. These hand-drawn maps (composed in Los Angeles during the 1940s) are scanned from one such copy.

The Turkish government's efforts to destroy the memory of Anatolia's Armenian population are both furthered and undermined by the widespread fascination with treasure hunting in rural Turkey. As discussed here, many people in southeastern Turkey are convinced that treasure lies buried in the foundations of ruined Armenian churches and monasteries. In searching for it, they inevitably destroy these monuments further, but also re-enforce the presence of the land's former inhabitants in popular memory.

Not a map, but a fantastic obituary of Lawrence of Arabia that appeared in the satirical paper Akbaba at the time of his death. Some highlights:

Istanbul is famous for its beauty, Ankara its will; Paris its liveliness, Viena its operas, Switzerland its Sanatoriums and England is famous for Lawrence.

In the deserts during the Great War the Turkish army's most feared microbe was him.

In Lawrence's death the world's gain is as great as England's loss. Now it is more possible for nations to love each other and work together for peace.

Lawrence's death. As with any great joy it isn't easy to believe the good news.

If Lawrence is really dead... in that case people face a new fear: the fear of the hereafter.

An early cold war propaganda map showing Turkey as part of the Northern Tier, surrounded by a menacing sea of red. I think this map offers a partial rebuke to our tendency to see the experience of World War One and the "Sevres Syndrome" as the source of all Turkey's modern day militarism and nationalist paranoia. Yes, Turkey emerged from World War One, not just the War for Independence but the CUP period as well, with a political culture marked by these phenomenon. But so did most of the world. In fact, compared to some of the European countries that embraced fascism, Turkey was less militarized and less intensely xenophobic in the Republican period. And to suggest that these impulses were waiting to erupt just below the surface, kept in check only by Ataturk's personal charisma, really does seem to ignore the contingency of history. I would argue that the experience of the Cold War, culminating in the 1980 coup, did more to enshrine these impulses in modern turkish political culture than did the social and political climate of Turkey's founding. In connecting the dots directly from 1919 to the present, it's easy to forget that Turkey spent almost a half century regionally isolated by Cold War geopolitics. There was the Soviet Union was to the North and East, Warsaw Pact Bulgaria to the West and the Soviet-aligned states of Iraq and Syria to the South. Too often now discussions of the Sevres Syndrome imply it's merely an outdated bit of paranoia that was kept alive for a hundred years by the cynically authoritarian Kemalist state. But other things happened during this time, and their impact shouldn't be overlooked.

This is not, of course, to deny that the war's negative legacy in these regards. An example can be found in this map, showing the area off limits to non-Muslims and foreigners in the early years of the Republic. It is a telling illustration of the tension that existed between the government's insistence that all Turkish citizens were Turks regardless of their religion or race and an alternative conception of national identity in which the only real Turks were Turkish-speaking Sunni Muslims. The accompanying document, also from the Cumhuriyet Arsivi, lists exceptions to this prohibition, including travelers on ferries going into or out of the city, passengers on organized tours and workers on commercial craft who did not disembark.

To end on a more somber non-cartographic note: Between 1916 And 1926, Istanbul’s Muslim residents – male and female, rich and poor -- began killing themselves at a quickly rising rate. Following a decade of fighting – the Balkan Wars, World War One, and the ensuing Greek-Turkish conflict – statistics published at the time show a jump in the number of documented suicides in all of the city's districts. It is a tragedy whose specific Turkish dimension has not been adequately discussed in the growing body of excellent work on the Ottoman experience of the Great War.

Finally, anyone interested in reading more deeply on the topics raised by these maps should check out the Ottoman History Podcast's World War One reading list, prepared by Heather Hughes:

World War I Reading List

The period of the First World War, which for Ottoman

historians usually extends from the beginning of fighting in 1914 to the

establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, is one of the most hotly

discussed topics in Ottoman historiography. It is connected to both the end of

the empire and and its division into nation states, as well as questions of

nationalism, imperialism, occupation, ethnic cleansing, and numerous aspects of

social, economic, and cultural history. On the occasion of WWI's centennial, here

is a list of important works that represent the historiographical issues and

debates related to the First World War in the Ottoman Empire.

Books:

Akçam, Taner. The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The

Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton, N.J:

Princeton University Press, 2012.

Aksakal, Mustafa. The Ottoman Road to War in 1914: The

Ottoman Empire and the First World War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press, 2008.

Antonius, George. The Arab Awakening: The Story of the

Arab National Movement. New York: Capricorn Books, 1965

Beşikçi, Mehmet. The Ottoman Mobilization of Manpower in

the First World War: Between Voluntarism and Resistance. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Bley, Helmut and Anorthe Kremers (eds). The World During

the First World War. Klartext Verlag : 2014.

Bloxham, Donald. The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism,

Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2005.

Çiçek, M T. War and State Formation in Syria: Cemal

Pasha's Governorate During World War I, 1914-1917. London; New York :

Routledge, 2014.

Criss, Bilge. Istanbul Under Allied Occupation, 1918-1923.

Leiden: Brill, 1999.

Edmonds, C J, and Yann Richard. East and West of Zagros:

Travel, War and Politics in Persia and Iraq 1913-1921. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the

Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: H. Holt,

2001.

Gingeras, Ryan. Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and

the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1912-1923. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2009.

Kant, Vedica. Journeying Through War: Colonial India and

the First World War, 1914 - 1918. S.l.: Roli Books Private Ltd, 2014.

Kévorkian, Raymond H. The Armenian Genocide: A Complete

History. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Köroğlu, Erol. Ottoman Propaganda and Turkish Identity:

Literature in Turkey During World War I. London Tauris, 2007.

Liebau, Heike. The World in World Wars: Experiences,

Perceptions and Perspectives from Africa and Asia. Leiden, the Netherlands:

Brill, 2010.

McCarthy, Justin. Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of

Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922. Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, 1995..

McMeekin, Sean. The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman

Empire and Germany's Bid for World Power. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of

Harvard University Press, 2010.

Rogan, Eugene. Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the

Middle East. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

Soldiers' Tales: Two Palestinian Jewish Soldiers in the

Ottoman Army During the First World War. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2013.

Sluglett, Peter. Britain in Iraq: Contriving King and

Country. London: I.B.Tauris, 2007.

Suny, Ronald G, Fatma M. Göçek, and Norman M. Naimark. A

Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Tachjian, Vahé. La France En Cilicie Et En

Haute-Mésopotamie: Aux Confins De La Turquie, De La Syrie Et De L'irak :

(1919-1933). Paris: Karthala, 2004.

Tamārī, Salīm. Year of the Locust: A Soldier's Diary and

the Erasure of Palestine's Ottoman Past. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2011.

Ṭaʼuber, Eliʻezer. The Arab Movements in World War I.

London: Frank Cass, 1993.

Tusan, Michelle E. Smyrna's Ashes: Humanitarianism,

Genocide, and the Birth of the Middle East. Berkeley : University of California

Press, 2012.

Ulrichsen, Kristian. The First World War in the Middle

East. London : Hurst, 2014.

Ulrichsen, Kristian. The Logistics and Politics of the

British Campaigns in the Middle East, 1914-22. Houndmills, Basingstoke,

Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Üngör, Uğur U. The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and

State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Yanikdağ, Yücel. Healing the Nation: Prisoners of War,

Medicine and Nationalism in Turkey, 1914-1939. Edinburgh : Edinburgh University

Press, 2013.

Zeidner, Robert F. The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The

French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922. Ankara: Atatürk Supreme Council for

Culture, Language and History, 2005.

General & Reference:

Das, Santanu. Race, Empire and First World War Writing.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Higham, Robin D. S, and Dennis E. Showalter. Researching

World War I: A Handbook. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2003.

Neiberg, Michael S. Fighting the Great War: A Global

History. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Articles:

Al-Qattan, Najwa. "When Mothers Ate Their Children:

Wartime Memory and the Language of Food in Syria and Lebanon."

International Journal of Middle East Studies 46.4 (2014): 719-736.

Akın, Yiğit. "War, Women, and the State: The Politics

of Sacrifice in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War." Journal Of

Women's History 26.3 (2014): 12-35.

Boyar, Ebru. “The Impact of the Balkan Wars on Ottoman

History Writing: Searching for a Soul.” Middle East Critique 23.2 (2014):

147-156.

Çetinkaya, Y. Doğan. "Atrocity Propaganda and the

Nationalization of the Masses in the Ottoman Empire During the Balkan Wars

(1912-1913). International Journal of Middle East Studies 46.4 (2014) :

759-778.

Ekmekcioglu, Lerna. 2013. "A Climate for Abduction, a

Climate for Redemption: The Politics of Inclusion During and After the Armenian

Genocide". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 55, no. 03:

522-553.

Ekmekçioğlu, Lerna. 2014. "Republic of Paradox: the

League of Nations Minority Protection Regime and the New Turkey's

Step-Citizens". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 46, no. 04:

657-679.

El Bakria, Alia. 2014. "“MEMORIES OF THE BELOVED”:

ORAL HISTORIES FROM THE 1916–19 SIEGE OF MEDINA". International Journal of

Middle East Studies. 46, no. 04: 703-718.

Gardner, Nikolas. "Morale And Discipline In A

Multiethnic Army: The Indian Army In Mesopotamia (1914–1917)." Journal Of

The Middle East & Africa 4.1 (2013): 1-20.

Jacobson, Abigail. (2008). “Negotiating Ottomanism in

Times of War: Jerusalem During World War I Through the Eyes of a Local Muslim

Resident. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 40, (2008): pp

69-88.

Kaplan, Sam. "Territorializing Armenians: Geo-Texts,

And Political Imaginaries In French-Occupied Cilicia, 1919-1922." History

& Anthropology 15.4 (2004): 399-423.

Owen, Roger. "British And French Military

Intelligence In Syria And Palestine, 1914-1918: Myths And Reality."

British Journal Of Middle Eastern Studies 38.1 (2011): 1-6.

Reibman, Max. 2014. "THE CASE OF WILLIAM YALE: CAIRO’S

SYRIANS AND THE ARAB ORIGINS OF AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN THE POST-OTTOMAN MIDDLE

EAST, 1917–19". Internatıonal Journal of Middle East Studies. 46, no. 04:

681-702.

Satia, Priya. "Developing Iraq: Britain, India And

The Redemption Of Empire And Technology In The First World War." Past

& Present 197.1 (2007): 211-255.

Schilcher, Linda. "Famine in Syria, 1915-1918"

in Problems of the Middle East in Historical Perspective: Essays in Honour of

Albert Hourani, eds. John P. Spagnolo and Albert Hourani (Reading: Ithaca

Press, 1996).

Shields, Sarah. "Mosul, The Ottoman Legacy And The

League Of Nations." International Journal Of Contemporary Iraqi Studies

3.2 (2009): 217-230. Academic Search Complete.

Sluglett, Peter. “The Waning of Empires: The British, the

Ottomans and the Russians in the Caucasus and North Iran, 1917–1921.” Middle

East Critique 23.2 (2014): 189-208.

Strohmeier, Martin. "Fakhri (Fahrettin) Paşa And The

End Of Ottoman Rule In Medina (1916-1919)." Turkish Historical Review 4.2

(2013): 192-223.

Watenpaugh, Keith David. “The League of Nations’ Rescue of

Armenian Genocide Survivors and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism,

1920–1927,” American Historical Review 115, 5 (2010): 1315–39.

Tanielian, Melanie Schulze. "FEEDING THE CITY: THE

BEIRUT MUNICIPALITY AND THE POLITICS OF FOOD DURING WORLD WAR I".

International Journal of Middle East Studies. 46, no. 04: 737-758.

Turan, Ömer. “Turkish Historiography of the First World

War.” Middle East Critique 23.2 (2014): 241-257.

Yiğit, Yücel. “The Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa and World War I.”

Middle East Critique 23.2 (2014): 157-174.

Zardykhan, Zharmukhamed. "Ottoman Kurds Of The First

World War Era: Reflections In Russian Sources." Middle Eastern Studies

42.1 (2006): 67-85.

- See more at:

http://www.ottomanhistorypodcast.com/p/books-and-bibliographies.html#sthash.0RI1MFFW.dpuf